«Egli si è rivestito di giustizia come di una corazza, e sul suo capo ha posto l’elmo della salvezza» (Is 59,17)

L’elmo è insieme oggetto e metafora, e viene dalla profondità del tempo. Quello in metallo, destinato a proteggere fisicamente la testa, risale al tempo dei Sumeri ( III millennio a.C.); prima era in cuoio, o stoffa. Aegishjalmur, anche conosciuto come Elmo dell’Orrore o Elmo dell’Impavido, è l’antico simbolo a cui i Vichinghi attribuivano il potere di fornire protezione e infondere paura nei cuori dei nemici. In Italia “l’Elmo di Scipio” è metafora centrale del nostro Inno Nazionale. Noto anche come elmo di Annibale, appartenne al celebre comandante Publio Cornelio Scipione; fu preda di guerra del generale cartaginese Annibale nel periodo delle guerre puniche, diventando l’emblema della grande sfida tra Roma e Cartagine e finendo per rappresentare il coraggio e la forza dei guerrieri di entrambe le fazioni. L’elmo appare anche in numerose leggende, storie e racconti popolari marittimi, solitamente come uno strumento che determina il destino delle navi e dei loro equipaggi. Queste storie spesso si concentrano sul tema della lotta umana contro le forze della natura, e l’elmo rappresenta la capacità umana di influenzare il proprio destino nonostante gli ostacoli esterni. ( https://symbolopedia.com/it/helm-symbolism-meaning/ ) .

Il valore simbolico di questo tipo di oggetto ragionevolmente deriva dal fatto che ripara la parte più fragile, misteriosa e vitale del corpo umano: la testa, il luogo fisico che ospita la parte immateriale dell’essere umano, il pensiero. Si può dire che è l’essenza identitaria di una persona, e da qui nasce la necessità di proteggerla ed insieme di riconoscerne l’importanza vitale. L’elmo è “oltre” la maschera – che copre solo il viso – perchè altera e protegge anche le parti meno visibili e misteriose della natura umana, tra cui il cervello. Nella tradizione biblica la valenza metaforica dell’elmo indica la stessa direzione, facendo parte delle armi di difesa di cui Dio riveste i suoi fedeli: ; Egli riveste i suoi fedeli con elmo, scudo, corazza e spada; lo scudo protegge il cuore e la corazza il corpo ma è l’elmo che protegge la testa, da cui provengono i pensieri. La metafora delle armi come simboli della protezione di cui Dio riveste il credente si chiarisce e rinnova nell’Apostolo Paolo; «Indossate l’armatura di Dio per poter resistere alle insidie del diavolo e spegnere le frecce infuocate del Maligno» (cfr. Ef 6,11-17). Agli Efesini raccomanda di «Prendere anche l’elmo della salvezza» (cfr. Ef 6,17a). Il verbo greco significa anche «accettare l’elmo della salvezza» implicando significativamente la necessità di accettare l’azione salvifica di Dio nell’ambito di un rapporto attivo tra Creatura e Creatore. L’elmo diventa quindi metafora di speranza, e non solo di difesa. Sempre Paolo, nella lettera ai Tessalonicesi, afferma : «Noi invece, che apparteniamo al giorno, siamo sobri, vestiti con la corazza della fede e della carità, avendo come elmo la speranza della salvezza» (cfr. 1Ts 5,8).

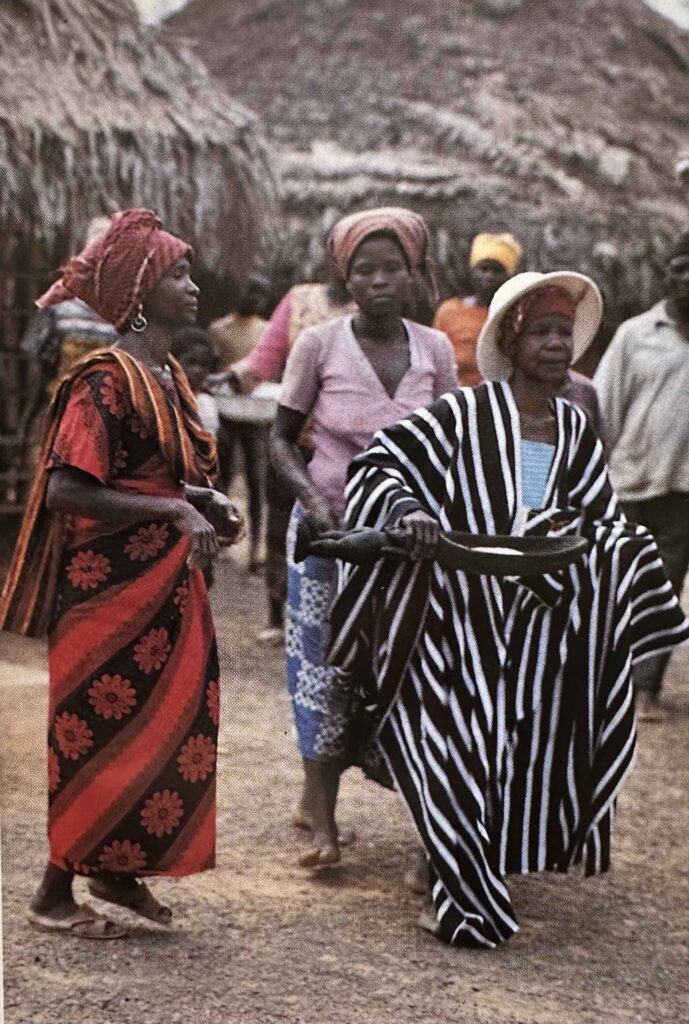

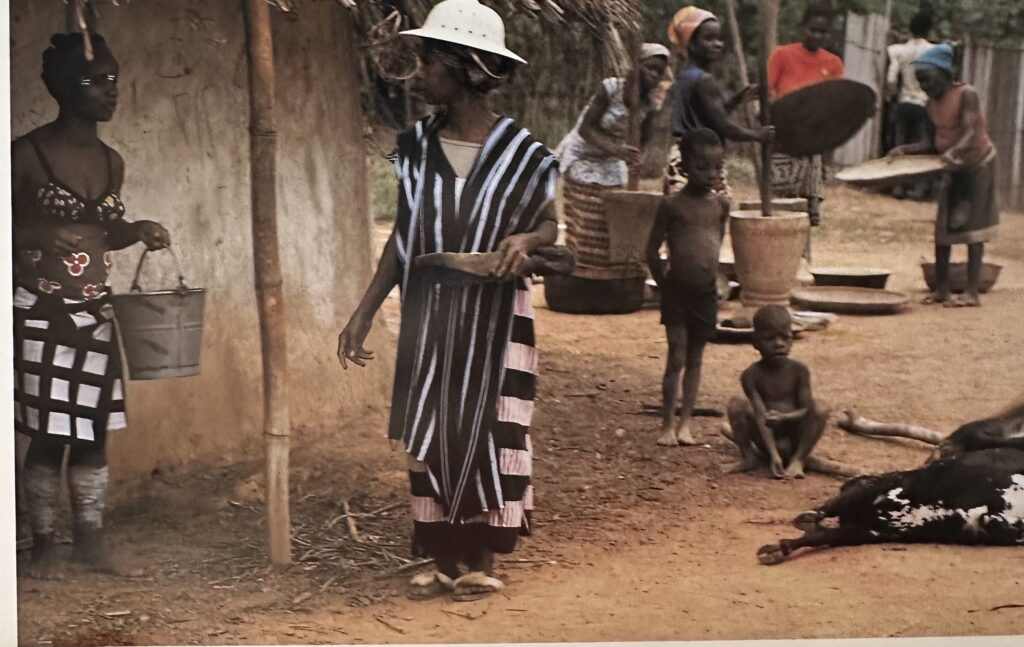

La storia più approfondita dell’elmo si può trovare qui ( https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/elmo/# ), ed è interessante notare che mentre i caschi militari contemporanei sono semplici dispositivi difensivi, fino all’inizio del secolo scorso essi “parlavano”, nel senso che oltre a svolgere la necessaria funzione protettiva erano arricchiti di forme, materiali o colori simbolici; l’esempio più eclatante è l’elmo Kabuto, in uso ai Samurai Giapponesi di alto rango ( https://temizen.zenworld.eu/paginezen/approfondimenti/kabuto-funzioni-e-simboli-dell-elmo-giapponese ). Anche una semplice e sommaria ricostruzione come questa consente di cogliere la dimensione archetipale che può assumere un semplice oggetto, se posto in una logica speculativa, ma è il porsi davanti alla declinazione dell’oggetto “elmo” che fanno le culture extraeuropee – e particolarmente quelle africane – a rendere evidente la potenza narrativa delle immagini e delle loro manifestazioni materiali.

Le maschere a elmo che abbiamo raccolto per questa esposizione sono profondamente differenti tra loro nel linguaggio estetico. Si va dalla astrazione essenziale della maschera ad elmo Mumuye alla potenza realistica dei caschi Bundu, ma nulla è lasciato al caso; ogni forma, colore, segno, la stessa materia usata, serve ad evocare uno stato di coscienza ed a comunicarlo, riannoda il filo perenne tra il reale e l’immaginato, l’immanente e il trascendente. Il dialogo con il nostro tempo ed il nostro mondo è affidato alla presenza di un casco usato nel gioco del Football Americano e precisamente dai Pirates 1984: Hard but fair, questa disciplina sportiva ha il pregio di subliminale gli istinti aggressivi indirizzandoli in un sistema di valori positivi.

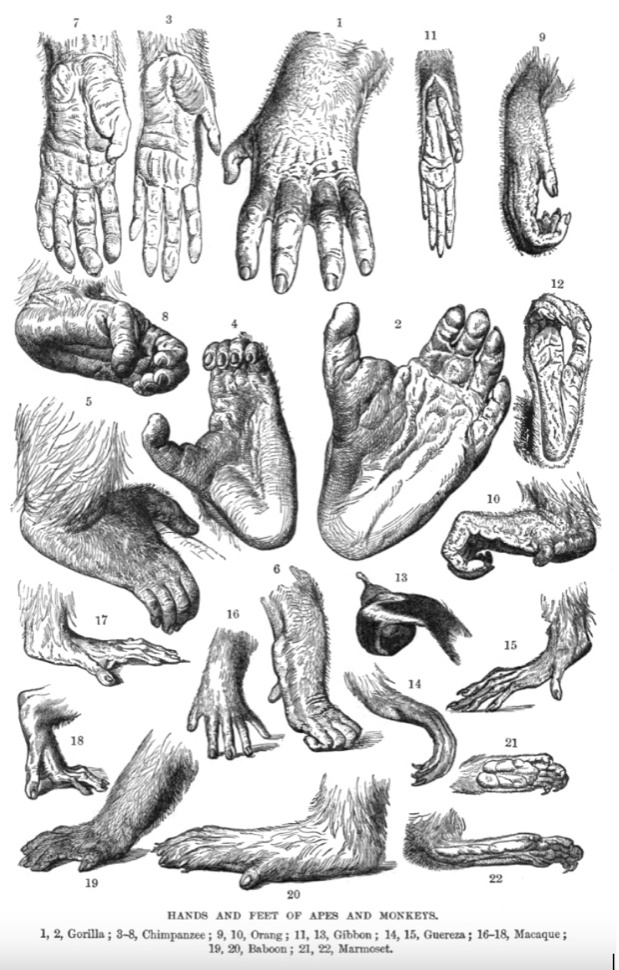

Le “Teste” di Rainer Kriester sono invece la formidabile traduzione nel linguaggio dell’arte moderna di quel misterioso linguaggio archetipale che impregna le opere provenienti da Continenti lontani: Non è un caso che il grande Maestro Tedesco, che scelse la nostra terra come Casa dell’ Anima, fosse così attento alle forme delle opere tradizionali Africane; chirurgo ( 1) delle forme artistiche viste attraverso i saperi assorbiti nei giovanili studi di medicina, Rainer osservava una maschera, una scultura, la interiorizzava d’istinto fermandola sulla carta, grazie alla sua grande abilità di acquerellista, ne fissava gli elementi fondanti per tradurli poi nella essenzialità del suo linguaggio artistico, che risulta così insieme sorprendentemente attuale ed emergente dalla profondità del tempo. Attenzione però! I linguaggi apparentemente lontani evocati dalle opere esposte parlano di vita e di morte, di amore e di sofferenza, parlano cioè anche di noi, e per noi. Ma bisogna volere, e sapere, vedere.

1) L’etimologia della parola chirurgo ha le sue radici nel dal greco χειρουργός (cheirourgos), formato da χείρ (cheir) = mano e da ἔργον (ergon) = opera; il chirurgo, quindi, è colui che opera con le mani).

“He has put on justice as a breastplate, and on his head he has placed the helmet of salvation” (Is 59:17)

The helmet is both an object and a metaphor, and comes from the depths of time. The metal one, intended to physically protect the head, dates back to the time of the Sumerians (3rd millennium BC); before that it was made of leather, or cloth. Aegishjalmur, also known as the Helmet of Horror or the Helmet of the Fearless, is the ancient symbol to which the Vikings attributed the power to provide protection and instill fear in the hearts of enemies. In Italy, “Scpio’s Helmet” is the central metaphor of our National Anthem. Also known as Hannibal’s helmet, it belonged to the famous commander Publius Cornelius Scipio; was a war booty of the Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Punic Wars, becoming the emblem of the great challenge between Rome and Carthage and ending up representing the courage and strength of the warriors of both factions.

The helmet also appears in numerous legends, stories and maritime folk tales, usually as an instrument that determines the fate of ships and their crews. These stories often focus on the theme of the human struggle against the forces of nature, and the helmet represents the human ability to influence one’s own destiny despite external obstacles. ( https://symbolopedia.com/it/helm-symbolism-meaning/ ) .

The symbolic value of this type of object reasonably derives from the fact that it protects the most fragile, mysterious and vital part of the human body: the head, the physical place that houses the immaterial part of the human being, thought. It can be said that it is the essence of a person’s identity, and from here comes the need to protect it and at the same time to recognize its vital importance. The helmet is “beyond” the mask – which only covers the face – because it also alters and protects the less visible and mysterious parts of human nature, including the brain.

In the biblical tradition, the metaphorical value of the helmet indicates the same direction, being part of the defensive weapons with which God clothes his faithful: He clothes his faithful with a helmet, shield, breastplate and sword; the shield protects the heart and the breastplate the body but it is the helmet that protects the head, from which thoughts come. The metaphor of the weapons as symbols of the protection with which God clothes the believer is clarified and renewed in the Apostle Paul; “Put on the full armour of God, that you may be able to resist the wiles of the devil and to extinguish the flaming arrows of the Evil One” (cf. Eph 6:11-17). He recommends to the Ephesians to “take also the helmet of salvation” (cf. Eph 6:17a). The Greek verb also means “to accept the helmet of salvation”, significantly implying the need to accept the saving action of God within an active relationship between Creature and Creator. The helmet thus becomes a metaphor for hope, and not just defense. Again Paul, in the letter to the Thessalonians, states: “But we who belong to the day, let us be sober, putting on the breastplate of faith and love, and for a helmet the hope of salvation” (see 1 Thess 5:8).

The more in-depth history of the helmet can be found here ( https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/elmo/# ), and it is interesting to note that while contemporary military helmets are simple defensive devices, until the beginning of the last century they “spoke”, in the sense that in addition to performing the necessary protective function they were enriched with symbolic shapes, materials or colors; the most striking example is the Kabuto helmet, used by high-ranking Japanese Samurai ( https://temizen.zenworld.eu/paginezen/approfondimenti/kabuto-funzioni-e-simboli-dell-elmo-giapponese ).

Even a simple and summary reconstruction like this allows us to grasp the archetypal dimension that a simple object can assume, if placed in a speculative logic, but it is placing ourselves in front of the declination of the “helmet” object that non-European cultures – and particularly African ones – do that makes the narrative power of images and their material manifestations evident.

The helmet masks that we have collected for this exhibition are profoundly different from each other in aesthetic language. They range from the essential abstraction of the Mumuye helmet mask to the realistic power of the Bundu helmets, but nothing is left to chance; every shape, color, sign, the same material used, serves to evoke a state of consciousness and to communicate it, re-ties the perennial thread between the real and the imagined, the immanent and the transcendent. The dialogue with our time and our world is entrusted to the presence of a helmet used in the game of American Football, and precisely from Pirates 1984. Hard but fair,

this sporting disciplinehas the merit of subliminalizing aggressive instincts by directing them into a system of positive values.

Rainer Kriester’s “Heads” are instead the formidable translation into the language of modern art of that mysterious archetypal language that permeates the works coming from distant continents: It is no coincidence that the great German Master, who chose our land as the Home of the Soul, was so attentive to the forms of traditional African works; a surgeon (1) of the artistic forms seen through the knowledge absorbed in his youthful medical studies, Rainer observed a mask, a sculpture, internalized it instinctively, stopping it on paper, thanks to his great skill as a watercolourist, he fixed its founding elements to then translate them into the essentiality of his artistic language, which thus appears both surprisingly current and emerging from the depths of time. But be careful! The apparently distant languages evoked by the works on display speak of life and death, love and suffering, that is, they also speak of us, and for us. But you have to want, and know, to see.

1) The etymology of the word surgeon has its roots in the Greek χειρουργός (cheiourgos), formed from χείρ (cheir) = hand and ἔργον (ergon) = work; the surgeon, therefore, is he who operates with his hands).

Giuliano Arnaldi, Onzo 16 ottobre 2024