“ L’uomo fu inizialmente nomade; oggi, assimilata la stanzialità ed a causa della mondializzazione, sta diventando “nomade” in un modo nuovo. I nomadi hanno inventato gli elementi basilari della civiltà; gli stanziali l’hanno organizzata. Chi si sposta non è detto che sia “barbaro” ma può essere una forza d’innovazione e di creazione; le società quando si chiudono agli itineranti, agli stranieri, a qualsiasi movimento, declinano. Con le nuove tecnologie del viaggio, reale o virtuale, si aprono nuovi scenari per l’umanità. Giunge a compimento l’egemonia dell’ultimo impero stanziale (gli USA), e incomincia la gara a rimpiazzarlo da parte delle tre forze nomadi di oggi: mercato, democrazia, fede”. Questo è l’incipit di un bel libro di Jaques ATTALI , L’UOMO NOMADE – SPIRALI 2006 – Pur essendo datato, nel senso che negli ultimi dieci anni i fenomeni migratori hanno assunto proporzioni e caratteristiche decisamente epocali, il testo di Attali definisce il perimetro dell’argomento.

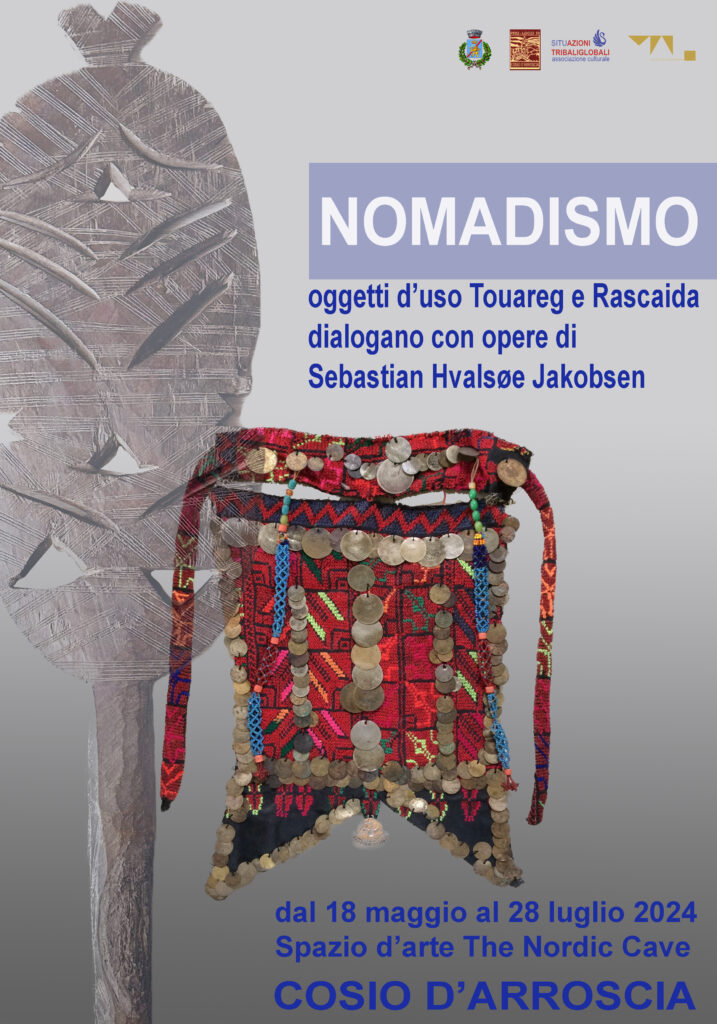

A noi interessa riflettere sulla dimensione estetica di quello che è il nomadismo per eccellenza, almeno nel nostro immaginario, ovvero quello che popola i deserti nord africani. Gli oggetti in uso presso quelle culture testimoniano la “ consueta” , sorprendente bellezza a cui ci hanno abituato le Arti Primarie. Nel caso dei picchetti Tuareg sono forma e segno a parlarci; quelli a forma piatta ed articolata si chiamano Ehel, sono posti all’interno delle tende per sostenere i pannelli Eseber – realizzati in fibra vegetale- e destinati a creare spazi intimi. I picchetti scolpiti a tutto tondo si chiamano Igem, sono posti all’esterno della tenda, ne indicano l’ingresso e ne identificano gli abitanti . Per i rari Burqua “Arouse” dei Rashaida è la fantasmagoria di materiali ed oggetti usati per creare questo particolare manufatto ad evocare antiche narrazioni. Questi particolari veli nuziali fanno riflettere sui pregiudizi che abbiamo verso le culture diverse dalla nostra; essendo Burqua, istintivamente ci rimandano all’idea di oppressione e svilimento della donna; non è così, ed è sufficiente vederli per rendersene conto, apprezzandone la varietà di colori, materiali preziosi, intrecci. Non è coprire il volto o il corpo ad essere opprimente, ma essere obbligate a farlo, e c’è molto meno rispetto verso la donna nella ostentazione mercificata del nudo che si fa in occidente.

Mentre i Touareg sono ampiamente conosciuti e per certi versi mitizzati, i Rashaida furono l’ultima minoranza a migrare in Eritrea nel XIX secolo dalla Penisola Arabica. I loro accampamenti sono prevalentemente presso Massawa, ed oggi possono essere considerati i testimoni dell’unica cultura eritrea interamente nomade e di lingua araba, fortemente tradizionalista. Di carattere schivo e guerriero, storicamente pirati e predoni , sono coloro che anticamente si occupavano della tratta degli schiavi e che ancora oggi gestiscono operativamente il transito nel deserto dei migranti, gli schiavi del XXI secolo.

“ Man was initially nomadic; today, having assimilated sedentary living and due to globalization, he is becoming “nomadic” in a new way. Nomads invented the basic elements of civilization; the residents organized it. Those who move are not necessarily “barbarian” but can be a force of innovation and creation; When societies close themselves to itinerants, to foreigners, to any movement, they decline. With new travel technologies, real or virtual, new scenarios are opening up for humanity. The hegemony of the last sedentary empire (the USA) comes to fruition, and the race to replace it by today’s three nomadic forces begins: market, democracy, faith”. This is the incipit of a beautiful book by Jaques ATTALI, L’UOMO NOMADE – SPIRALS 2006 – Despite being dated, in the sense that in the last ten years migratory phenomena have taken on decidedly epochal proportions and characteristics, Attali’s text defines the perimeter of the topic.

We are interested in reflecting on the aesthetic dimension of what is the nomadism par excellence, at least in our imagination, that is, that which populates the North African deserts. The objects in use in those cultures bear witness to the “usual”, surprising beauty to which the Primary Arts have accustomed us. In the case of the Tuareg pickets, it is the shape and sign that speak to us; those with a flat and articulated shape are called Ehel, they are placed inside the tents to support the Eseber panels – made of vegetable fiber – and intended to create intimate spaces. The all-round sculpted pegs are called Igem, they are placed outside the tent, they indicate the entrance and identify its inhabitants. For the rare Rashaida Burqua “Arouse” it is the phantasmagoria of materials and objects used to create this particular artefact that evokes ancient narratives. These particular wedding veils make us reflect on the prejudices we have towards cultures different from ours; being Burqua, they instinctively refer us to the idea of oppression and debasement of women; this is not the case, and it is enough to see them to realize this, appreciating the variety of colours, precious materials and weaves. It is not covering the face or the body that is oppressive, but being forced to do so, and there is much less respect towards women in the commodified ostentation of nudity that is done in the West.

While the Touareg are widely known and in some ways mythologized, the Rashaida were the last minority to migrate to Eritrea in the 19th century from the Arabian Peninsula. Their camps are mainly near Massawa, and today they can be considered the witnesses of the only entirely nomadic and Arabic-speaking, strongly traditionalist Eritrean culture. Of a shy and warrior nature, historically pirates and raiders, they are those who in ancient times dealt with the slave trade and who still today operationally manage the transit of migrants in the desert, the slaves of the 21st century.

Giuliano ARNALDI, Onzo. 17 Maggio 2024

clicca qui per vedere le opere esposte https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjBqAcY