https://flic.kr/s/aHskkzNvuX clicca qui per vedere la collezione

Per la presentazione della nostra collezione di pettini ho scelto una frase di Leonardo Sciascia; definisce in modo caustico ed essenziale l’importanza che riconosciamo a questo piccolo oggetto d’uso quotidiano, ne svela il profondo significato simbolico e concettuale. Come nasce un pensiero, o meglio, come nasce il pensiero, come si evolve fino a diventare un sistema complesso ed articolato che diventa cultura? Si può certamente dire che fino dall’antichità più remota l’osservazione di gesti istintivi fondamentali per la sopravvivenza , l’interiorizzazione del loro manifestarsi che ne qualifica l’utilità funzionale, sono l’insieme fondante del processo di conoscenza . Osservare, comprendere, astrarre e concettualizzare una esperienza ponendola in relazione ad altre, rende quella esperienza patrimonio culturale. E l’essere umano è sempre partito dal proprio corpo, dal modo in cui esso si fa strumento per governare il mondo circostante fin dalle azioni più semplici.

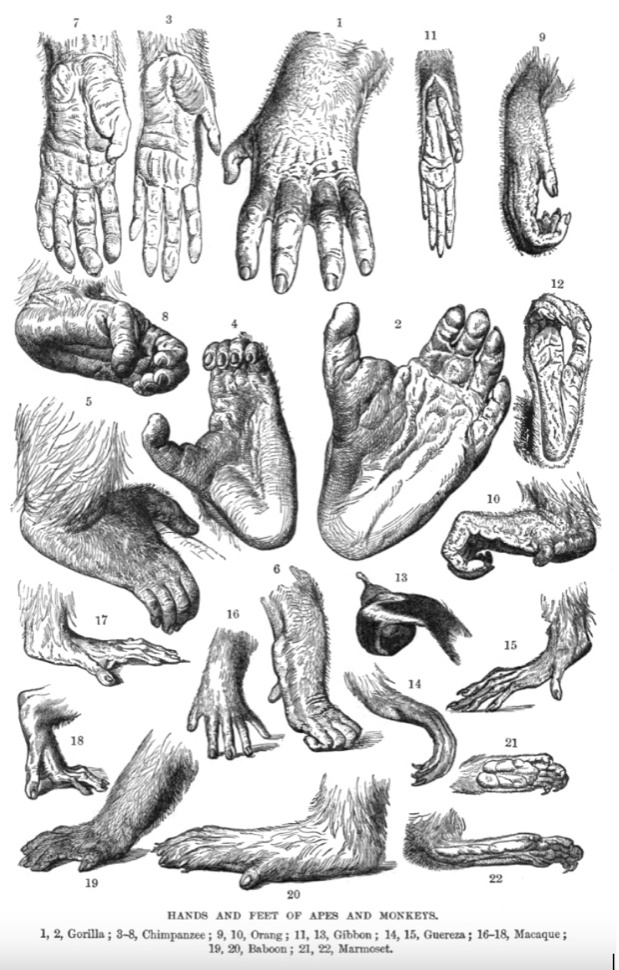

Pensate alla mano, primo strumento che districa i peli incolti del primate ( e poi dell’uomo), che lo aiuta ad aprirsi un varco nella radura. Probabilmente il primo pettine è nato così, realizzato da qualcuno che osservò la propria mano e la riprodusse nella forma, che parte spessa e solida per dipanarsi in una serie di elementi appuntiti. Come la mano districa i capelli, apre la strada nella foresta, i denti del pettine mettono ordine nei capelli e li liberano da parassiti. E non deve essere un caso che gli elementi terminali del pettine siano chiamati da sempre denti.

I pettini presentati in questa pubblicazione provengono da aree geografiche e culturali profondamente diverse tra loro. Africa, Oceania e Indonesia, India. il linguaggio estetico, i materiali usati, i riferimenti simbolici ne dichiarano l’appartenenza culturale e geografica, ma hanno origine comune.

Osserva Donatella Dolcini, Professore Ordinario di Lingua Hindi e Cultura Indiana presso Università Statale Milano (UNIMI) nel catalogo che presentò la collezione di pettini raccolta da Giuseppe Berger : “Al pari di dita/unghie, anche i denti svolgono una funzione di primaria importanza nel ritmo quotidiano della vita dell’uomo, permettendogli di incidere il cibo così da ridurlo immediatamente da un complesso unico e coeso – difficile da inghiottire, grande o piccolo che sia – a uno almeno grossolanamente parcellizzato. In sostanza, una variante del gioco delle dita che dividono un unico blocco in porzioni (strisce) più minute e agevoli da gestire. E infine l’elaborazione del pettine, dal mero uso primario, direttamente disceso dall’analogia con la mano, a quello mediato dalla dentatura, giunge a quel terzo stadio, immancabile nei processi di manifattura dell’uomo, che è il lato estetico. La mano-pettine, che in seconda battuta aveva incorporato anche l’imitazione della funzione dentaria, diventa alla fine un oggetto ancora più evoluto, in cui si manifesta non più solo la concreta estensione tecnologica di organi naturali, ma anche il libero apporto della creatività umana. Così la forma del pettine si abbellisce con l’eventuale aggiunta di un manico più o meno elaborato e di ghirigori che vanno ad impreziosire l’impugnatura, e modifica la propria misura fino a diventare il pettinino, un grazioso e aggraziato complemento della toilette e dell’abbigliamento soprattutto femminile.“

Il valore insieme semplice e profondo di questo tipo di oggetti è sorprendente, manifesta in modo netto la capacità umana di elaborare esperienze e migliorarle costantemente mediante un perfezionamento tecno logico che non è prodotto da macchine ma dall’ingegno. Ed è altrettanto sorprendente la necessità di rendere l’oggetto non solo funzionale ma anche bello, caricandolo di contenuti simbolici evocativi che spesso sono destinati ad amplificarne metaforicamente la funzione. Nei pettini delle culture Ivoriane, in gran parte raccolte da Giovanni Franco Scanzi negli anni sessanta del secolo scorso, l’elemento identitario è evidente. Le forme rimandano a figure di Antenati Ancestrali, oggetti sacri, animali il cui potere energetico, per il tramite dell’oggetti, potrà aiutare chi lo usa. Nel caso degli antichi pettini in avorio provenienti dalla Collezione Berger, in gran parte “scritti” con la figura di Ganesh, sempre Dolcini nota giustamente “Forse la ricorrente iconografia sul pettinino del dio elefante (Ganesh appunto) potrebbe collegarsi all’immagine simbolica che la capacità del pachiderma a farsi largo nella fitta vegetazione della giungla, penetrandovi dentro, suscita riguardo al figlio di Shiva, adorato infatti anche come rimovitore degli ostacoli.“

For the presentation of our collection of combs I chose a phrase from the Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia; defines in a caustic and essential way the importance we recognize in this small object of everyday use, revealing its profound symbolic and conceptual meaning.

How does a thought arise, or rather, how does thought arise, how does it evolve to become a complex and articulated system that becomes culture? It can certainly be said that the observation of instinctive gestures fundamental for survival since the most remote antiquity, the internalization of their manifestation, the fundamental elements that qualify their functional usefulness are the founding whole of the knowledge process. Observing, understanding, abstracting and conceptualizing an experience by placing it in relation to others makes that experience cultural heritage. And the human being has always started from his own body, from the way in which it becomes an instrument to govern the surrounding world starting from the simplest actions.

Think of the hand, the first tool that untangles the unkempt hair of the primate (and then of man), which helps him to open a path in the clearing. The first comb was probably born like this, made by someone who observed his own hand and reproduced its shape, which starts out thick and solid and then unravels into a series of pointed elements. As the hand untangles the hair, opens the way in the forest, the teeth of the comb tidy up the hair and free it from parasites. And it must not be a coincidence that the terminal elements of the comb have always been called teeth. The combs presented in this publication come from profoundly different geographical and cultural areas. Africa, Oceania and Indonesia, India. the aesthetic language, the materials used, the symbolic references declare their cultural and geographical belonging, but they have a common origin.

Donatella Dolcini, Full Professor of Hindi Language and Indian Culture at the Milan State University (UNIMI) observes in the catalog that presented the collection of combs collected by Giuseppe Berger: “Like fingers/nails, teeth also perform a function of primary importance in daily rhythm of man’s life, allowing him to affect food so as to immediately reduce it from a single and cohesive complex – difficult to swallow, large or small – to one that is at least roughly fragmented. In essence, a variant of the game of fingers that divide a single block into smaller and easier to manage portions (strips). And finally the development of the comb, from the mere primary use, directly descended from the analogy with the hand, to that mediated by the teeth, reaches that third stage, inevitable in man’s manufacturing processes, which is the aesthetic side. The hand-comb, which subsequently also incorporated the imitation of the dental function, ultimately becomes an even more evolved object, in which not only the concrete technological extension of natural organs is manifested, but also the free contribution of creativity Human. Thus the shape of the comb is embellished with the possible addition of a more or less elaborate handle and curlicues that embellish the handle, and changes its size until it becomes the comb, a graceful and graceful complement to the toilet and the ‘especially women’s clothing.“

The simple and profound value of this type of object is surprising, it clearly demonstrates the human ability to process experiences and constantly improve them through technological improvement that is not produced by machines but by ingenuity. And equally surprising is the need to make the object not only functional but also beautiful, loading it with evocative symbolic contents which are often intended to metaphorically amplify its function.

In the combs of the Ivorian cultures, largely collected by Giovanni Franco Scanzi in the sixties of the last century, the element of identity is evident. The shapes refer to figures of Ancestral Ancestors, sacred objects, animals whose energetic power, through the objects, can help those who use it. In the case of the ancient ivory combs from the Berger Collection, largely “written” with the figure of Ganesh, Dolcini rightly notes “Perhaps the recurring iconography on the comb of the elephant god (Ganesh precisely) could be connected to the symbolic image that the pachyderm’s ability to make its way through the dense vegetation of the jungle, penetrating it, arouses respect for the son of Shiva, who is also worshiped as a remover of obstacles.“

Giuliano Arnaldi, Onzo 21 settembre 2023