tra Cosio d'Arroscia e Onzo, passando per Vendone e....

Ansgar Elde, Ceramica . 1990

le opere esposte sono visibili qui https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjBENLb

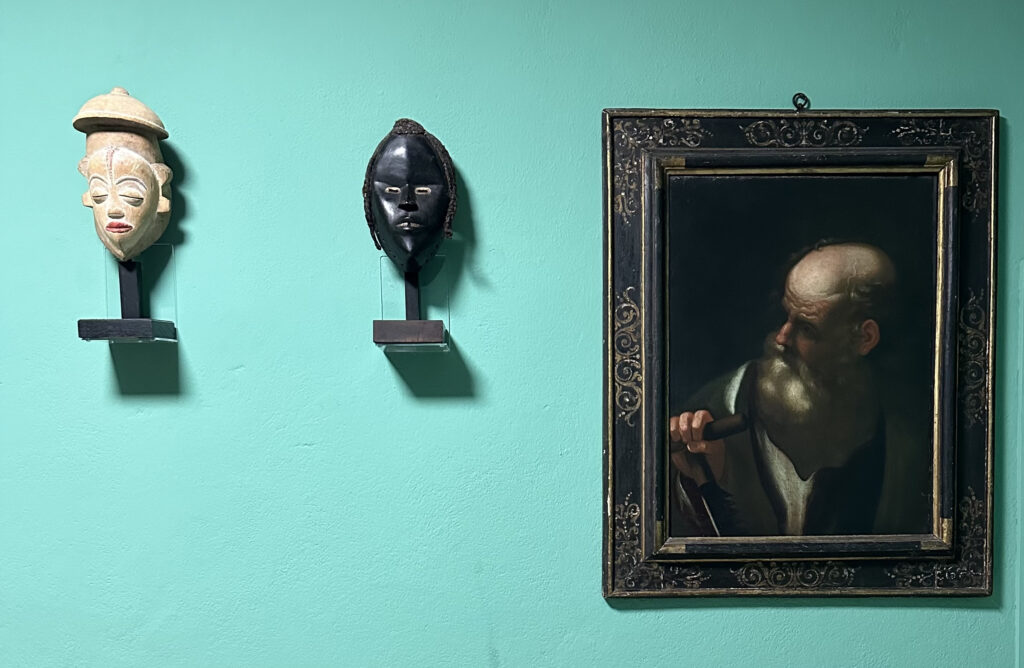

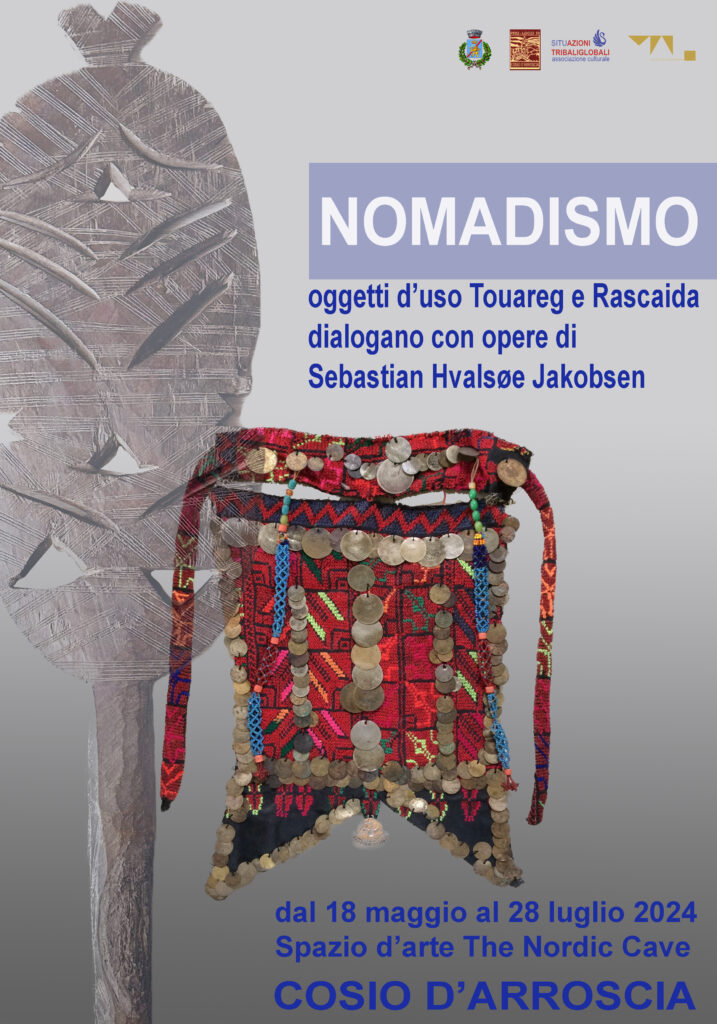

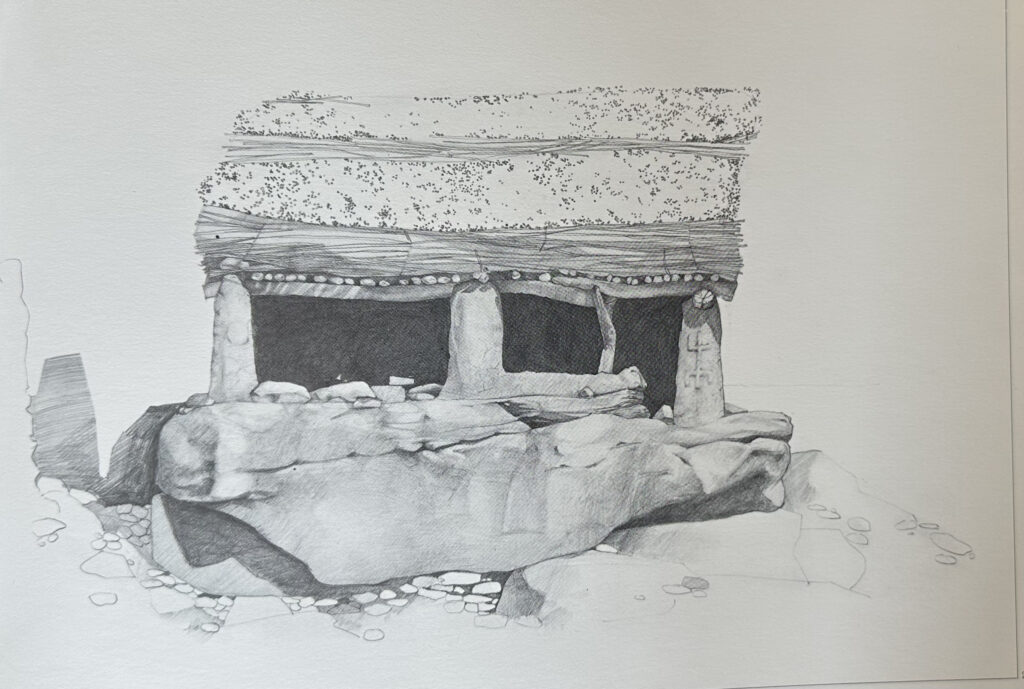

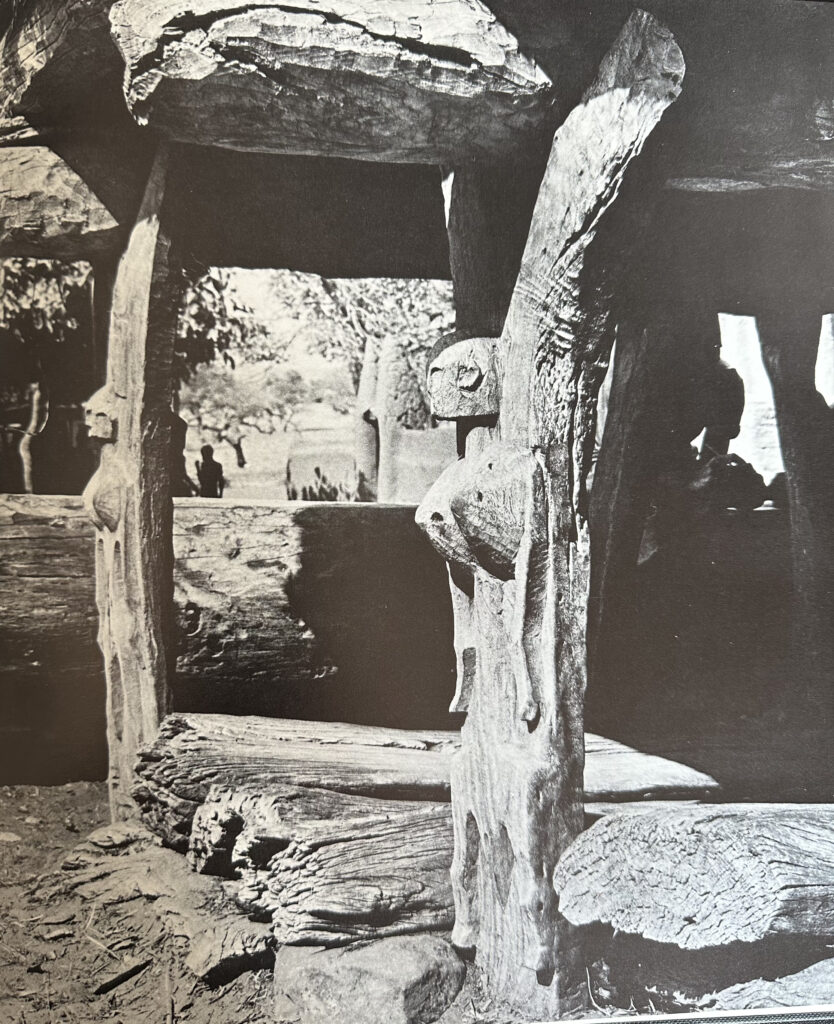

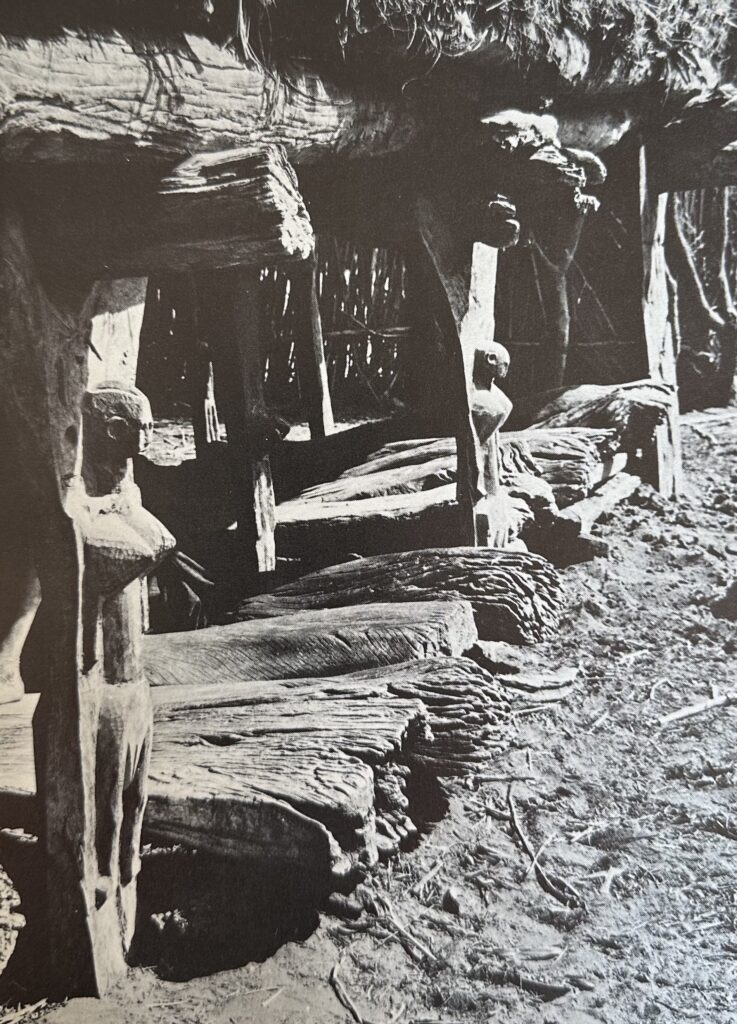

Nasce nella Valle Arroscia un ” Jardin Situationniste”, format ispirato al fortunato libro di Asger Jorn ” Le Jardin d’Albisola”. La rete di spazi espositivi organizzata dalle Associazioni MAP museo di Arti Primarie e SituaZioni Tribaliglobali ospita un insieme di eventi legati alla esperienza artistica e culturale attiva nella seconda metà del secolo scorso nella Liguria di Ponente, tra Albisola e Cosio d’Arroscia. Tra Onzo e Cosio, dove sono già esposte in modo permanente opere di Alechinsky, Appel, Corneille, Jorn, Vandercam, Rainer Kriester e Henry Moore, sono visibili fino al 30 ottobre 2024 opere di Carlos Carlè, Asgar Elde, Enzo L’Acqua e Saba Telli. Le opere d’arte moderna sono esposte in dialogo permanente con opere di arte tradizionale extraeuropea provenienti da Africa, Asia, Indonesia, Oceania . E’ possibile consultare una corposa biblioteca di settore, ed ogni evento è supportato da cataloghi consultabili anche on line. . La direzione artistica degli eventi è di Giuliano Arnaldi.

Où est le jardin.. ?

Un filo rosso mai spezzato lega la creatività di artisti che per tutto il Novecento scelsero quel triangolo magico tra Albisola, Calice Ligure e Cosio d’Arroscia come speciale casa dell’anima. Non solo i Futuristi, Lam, Fontana, Jorn – per citare i più “blasonati” – ma un popolo di creativi respirò quel soffio vitale, e diede un corpo alla propria immaginazione . La loro storia è forse ancora troppo ristretta nei confini del collezionismo locale, mentre risulterebbe di grande interesse generale per capire cosa accadde in quegli anni, ben oltre i confini locali. La storia dei Situazionisti è in questo senso emblematica; quel vento potente partì da Cosio d’Arroscia ma incendiò prima Parigi e poi il mondo intero, prova provata che l’arte non è solo un grazioso orpello ma formidabile energia sovversiva. Nel “Jardin” che abbiamo creato tra Cosio e Onzo, ne trovate alcuni, e ne troverete sempre più; nei limiti delle nostre possibilità l’intenzione è quella di creare dei “focus”, delle sintetiche retrospettive su singoli Artisti, senza alcuna pretesa se non quella di accendere una luce.” L’evento è iniziato domenica 1 settembre a Onzo presso la Locanda Tribaleglobale con Saba telli, che quell’epoca la visse con rara intensità e la testimoniò con ancor più rara bellezza, attraverso la sua vita e il suo lavoro; in consultazione anche alcuni rari cataloghi e testi legati al lavoro dell’Artista, provenienti da una collezione privata savonese, ed è in preparazione un catalogo che raccoglie la rara ed inedita documentazione; Dal 15 settembre a Cosio d’Arroscia la galleria derive ospita una “reunion” – come usa dire oggi- di alcuni tra i più interessati manipolatori di materie di quegli anni: Carlos Carlè, Asgar Elde, Enzo L’Acqua e lo stesso Sabatelli per l’aspetto ceramico.

A “Jardin Situationniste” is born in the Arroscia Valley, a format inspired by the successful book by Asger Jorn “Le Jardin d’Albisola”. The network of exhibition spaces organized by the Associations MAP museo di Arti Primarie and SituaZioni Tribaliglobali hosts a series of events linked to the artistic and cultural experience active in the second half of the last century in Western Liguria, between Albisola and Cosio d’Arroscia. Between Onzo and Cosio, where works by Alechinsky, Appel, Corneille, Jorn, Vandercam, Rainer Kriester and Henry Moore are already permanently exhibited, works by Carlos Carlè, Asgar Elde, Enzo L’Acqua and Saba Telli are visible until 30 October 2024. The modern works of art are exhibited in permanent dialogue with works of traditional non-European art from Africa, Asia, Indonesia, Oceania. It is possible to consult a substantial sector library, and each event is supported by catalogues that can also be consulted online. The artistic direction of the events is by Giuliano Arnaldi.

Où est le jardin.. ?

An unbroken red thread links the creativity of artists who throughout the twentieth century chose that magical triangle between Albisola, Calice Ligure and Cosio d’Arroscia as a special home for the soul. Not only the Futurists, Lam, Fontana, Jorn – to name the most “noble” – but a population of creatives breathed that vital breath, and gave a body to their imagination. Their story is perhaps still too narrow within the confines of local collecting, while it would be of great general interest to understand what happened in those years, well beyond the local borders. The story of the Situationists is emblematic in this sense; that powerful wind started from Cosio d’Arroscia but first set Paris on fire and then the entire world, proof that art is not just a pretty tinsel but a formidable subversive energy. In the “Jardin” that we have created between Cosio and Onzo, you will find some, and you will always find more; to the extent of our possibilities, the intention is to create “focuses”, synthetic retrospectives on individual Artists, without any pretension other than that of turning on a light.” The event began on Sunday 1 September in Onzo at the Locanda Tribaleglobale with Sabatelli, who lived that era with rare intensity and bore witness to it with even rarer beauty, through his life and his work; some rare catalogues and texts related to the Artist’s work, from a private collection in Savona, were also available for consultation, and a catalogue is being prepared that collects the rare and unpublished documentation; From 15 September in Cosio d’Arroscia the Derive gallery hosts a “reunion” – as they say today – of some of the most interested manipulators of materials of those years: Carlos Carlè, Asgar Elde, Enzo L’Acqua and Sabatelli himself for the ceramic aspect.