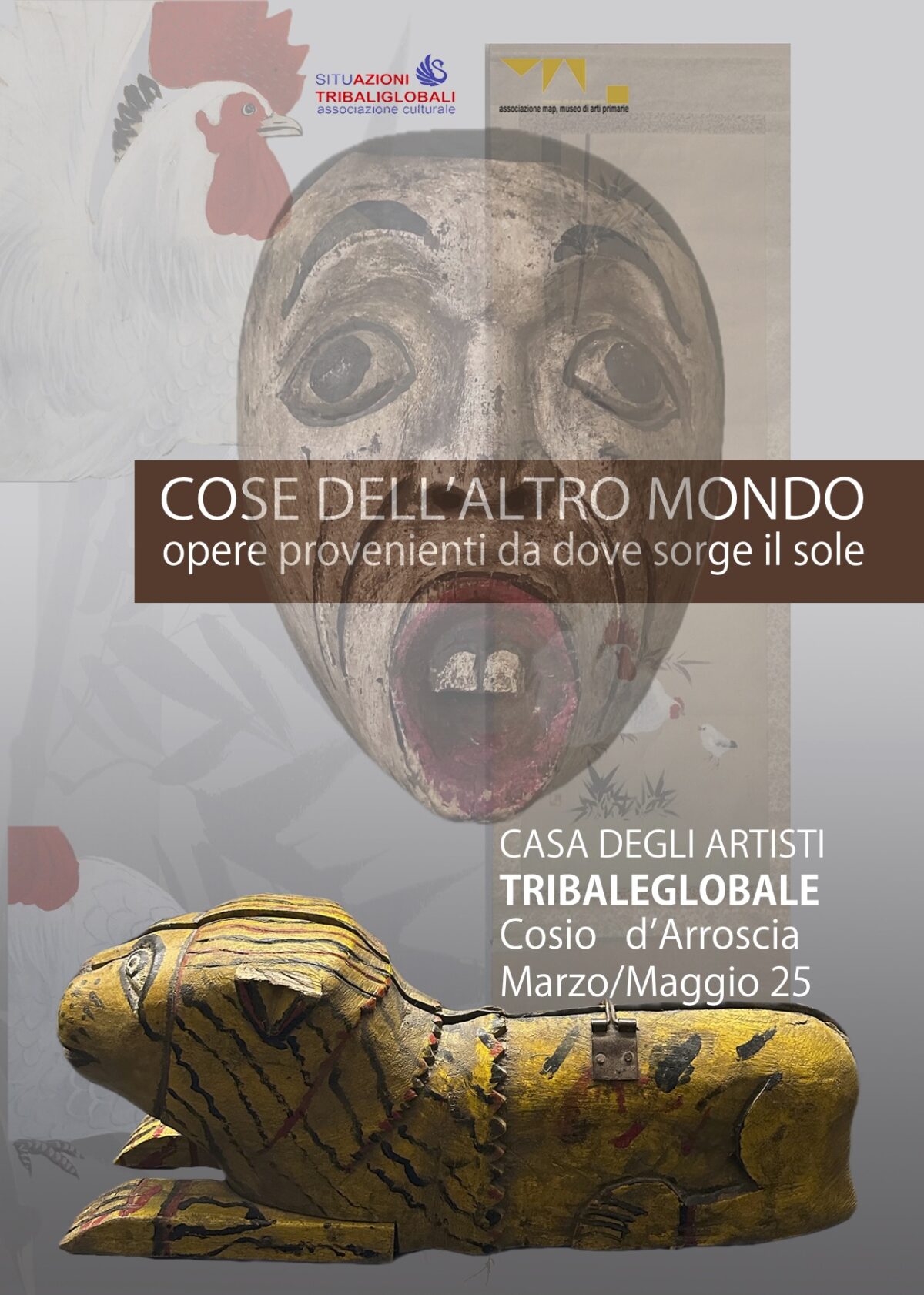

COSE DELL’ALTRO MONDO

Una selezione di opere provenienti da dove sorge il sole

“ Si vuole che la parola Asia derivi da una voce semitica (p. es. l’assiro Açu) significante “oriente”, e che sarebbe stata usata dai Fenici e dai Greci per indicare il Paese d’Oriente, in contrapposto a Europa (Ereb), Paese d’Occidente; ma tale etimologia è tutt’altro che sicura, e l’origine del nome Asia, come quella di gran parte dei nomi geografici antichi, è da considerarsi tuttora ignota.” ( treccani.it)

La Storia sta rimescolando le carte, ed Ereb sembra perdere la partita. Senza addentrarci in complesse analisi geopolitiche appare evidente la crisi del nostro mondo, crisi morale prima che economica. Non facciamo più figli, non crediamo più a nulla che non sia spettacolo e merce..Il “deus ex machina” (1) che Euripide e gli altri tragediografi Greci facevano apparire in momenti in cui la rappresentazione del dramma richiedeva un intervento divino autorevole e risolutore, oggi è il nome di un progetto usato in Svizzera per definire un inquietante esperimento di intelligenza artificiale: a Lucerna una chiesa ha deciso di installare un “Gesù AI” capace di dialogare con i fedeli in 100 lingue, e per due mesi, oltre 1.000 persone hanno interagito con questo avatar . Pare che non pochi fedeli l’abbiano considerata una esperienza mistica; il sistema di valori laico non è messo meglio, è sufficiente ascoltare Trump o più banalmente andare al bar e sentire cosa dice la gente per rendersi conto che libertà, democrazia, cultura sono quotidianamente schiacciati dal “tacco 12” della signora Santanchè.

Cina e India si avviano a conquistare una supremazia economica e geopolitica che porterà con se inesorabilmente un ripensamento della visione complessiva del mondo, e sopratutto della presenza in esso dell’umanità. Forse è il momento di iniziare a capire le origini di quelle culture, e noi proviamo a farlo esponendo una piccola ma non insignificante raccolta di opere d’arte che provengono da quelle culture.

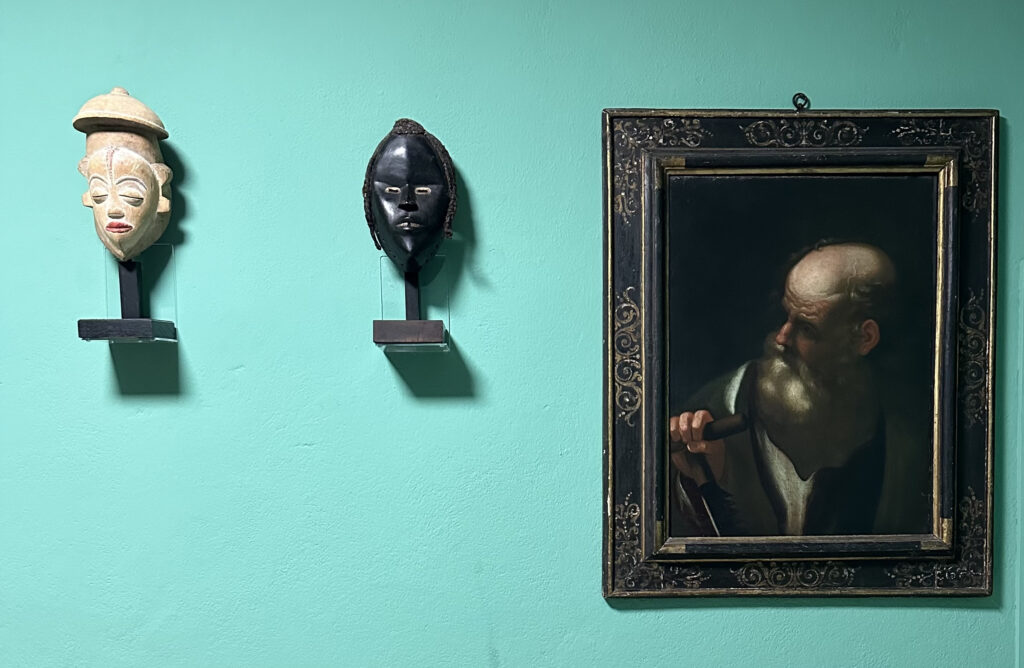

Abbiamo scelto opere diverse , con provenienze culturali diverse.

Nella Casa degli Artisti di Cosio d’Arroscia troverete tra l’altro:

- Una selezione di Kakemono ( 2 ); questi dipinti, così ricchi di valore mistico e simbolico, sono a nostro avviso una interessante testimonianza di come il Giappone abbia assorbito, interiorizzato ed arricchito l’influsso culturale determinante proveniente da Cina e Corea

- Alcuni oggetti provenienti dall’India, prevalentemente dal Rajasthan, raccolti a partire dagli anni sessanta del secolo scorso da Giuseppe Berger, probabilmente il più interessante collezionista di opere d’arte provenienti dall’India. Potrete vedere oggetti d’uso quotidiano, – giochi, utensili- elementi architettonici rituali, importanti bronzi rituali legati al culto di Virabhadra. Questi oggetti introducono tra l’altro una esposizione ben più ampia che si terrà entro la fine del 2025 negli spazi dei #magazzinidelMap a Villanova d’Albenga, dove esporremo, tra l’altro oltre 140 bronzi provenienti dalla #CollezioneBerger .

- Una collezione di maschere usate per la danza rituale Topeng.( 4 )

- 1) Deus ex machina è una frase latina mutuata dal greco “mechanè“, in greco antico: ἀπὸ μηχανῆς θεός? (“apò mēchanḗs theós“) che significa letteralmente “divinità (che scende) dalla macchina”.[1] Originariamente, indica un personaggio della tragedia greca, ovvero una divinità che compare sulla scena per dare una risoluzione ad una trama ormai non risolvibile secondo i classici principi di causa ed effetto. fonte https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deus_ex_machina

- 2) Il kakemono (掛物? letteralmente “cosa appesa”), o kakejiku (掛軸?), è un dipinto o una calligrafia giapponese, su seta, cotone o carta, organizzato a guisa di rotolo e destinato a essere appeso. A differenza dell’emakimono, un rotolo che viene aperto in senso orizzontale su una superficie, il kakemono si apre in verticale ed è concepito come decorazione murale da interno. Viene spesso esposto nel tokonoma. Essendo collegato a periodi specifici dell’anno o a occasioni particolari è esposto solo temporaneamente e poi riposto, accuratamente arrotolato, in apposite scatole oppure sostituito da un altro kakemono più appropriato alla nuova data (vi sono famiglie giapponesi che ne possiedono in gran numero, addirittura centinaia). fonte Wikipedia

- 3) Virabhadra non significa “guerriero”, ma è un nome proprio, di una divinità, composto da due termini: Vira e Bhadra. Il primo, Vira ( वीर ) significa eroe, uomo coraggioso, figlio maschio, eroismo, sacro fuoco rituale. Una connessione meravigliosa è la comune origine di questo termine con il latino Vir, uomo, da cui deriva appunto l’italiano virile. Sanscrito, latino, italiano e indi hanno infatti una comune origine tra le genti indoeuropee che 3-4.000 anni fa popolavano l’asia centrale e sono numerosi i termini che hanno uguale radice. Usciremmo dal tema di questo articolo, ma basti ricordare che madre in latino si dice mater e in sanscrito mata, così come il fuoco che in latino è igni, diviene agni in sanscrito, come il Dio Agni, eccetera, eccetera. Virasana, la posizione dell’eroe, è però una posizione molto differente da Virabhadrasana, e si esegue seduti. Il secondo, Bhadra (भद्र), significa buono, benevolo, di buon auspicio, bello, felice, grandioso, ma anche ferro, acciaio, oro, prosperità e vari altri concetti. Il sanscrito è infatti una lingua che è stata utilizzata per migliaia di anni praticamente invariata, un caso abbastanza raro nel panorama linguistico, in quanto divenne lingua rituale (altra analogia con il latino), e quindi i termini hanno sovente moltissimi diversi significati. Questa caratteristica unita al tema mistico della maggioranza dei testi, non ne facilita la chiarezza, ma proprio qui nasce la ricchezza e la bellezza interpretativa della sua letteratura.( fonte https://www.yogamagazine.it/2016/10/il-mito-dietro-le-asana-virabhadra-il.html )

- 4) Si veda https://giulianoarnaldi.blogspot.com/2024/08/topeng-la-forma-formante-topeng-forming.html

qui puoi vedere un tour virtuale