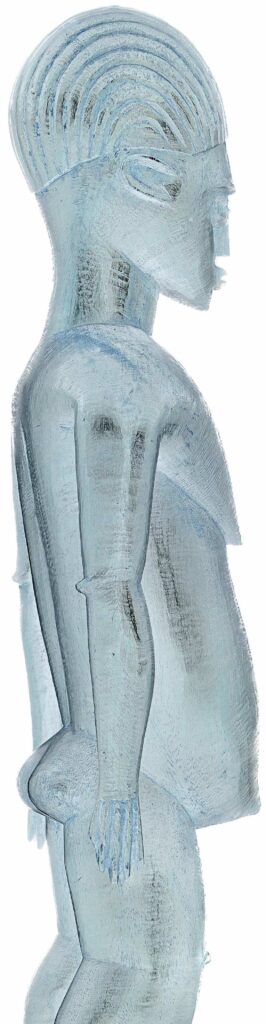

Maschera ad elmo Chiwara/ Sogolikun. Cultura Bamana, Mali.

Legno. Cm 46 Provenienza collezione privata, Spagna, Native Auction.

( Il nome Sogonikun è dato a un tipo di cimiero e figura mascherata che apparve a Wasolon e fu adottato nelle regioni vicine. ). Per un esemplare molto simile si veda Sotheby’s, NYC 7557 pag 23 figura 17

La vita sociale, economica e spirituale dei Bamana, nel sud-ovest del Mali, è governata da sei società di iniziazione conosciute collettivamente come dyow (sing. dyo). Le sei società sono n’domo, komo, nama, kono, chi wara e kore. Un Bamana deve passare rispettivamente attraverso tutte e sei i livelli di iniziazione per essere considerato un uomo completo con una visione completa degli insegnamenti e delle tradizioni ancestrali.

Ogni società di iniziazione ha il proprio tipo di maschera associato (per lo più zoomorfa, cioè basata su forme animali) tra cui i copricapi agricoli di antilopi chi wara (chiamato anche ci wara / tyi wara che significa ‘animale selvatico al lavoro’) dyo. L’obiettivo principale del chiwara dyo è quello di educare gli uomini alle migliori pratiche agricole e di onorare Chi Wara, l’eroe culturale dei Bamana, che ha creato le conoscenze relative alla coltivazione della terra ai Bamana. I membri del chi wara dyo si esibiscono in danze mascherate non solo per celebrare il loro mito, Chi Wara, ma anche per garantire la fertilità dei loro campi e pregare gli dei per un buon raccolto. Le celebrazioni vengono utilizzate anche per riconoscere pubblicamente l’esperienza degli agricoltori di successo.

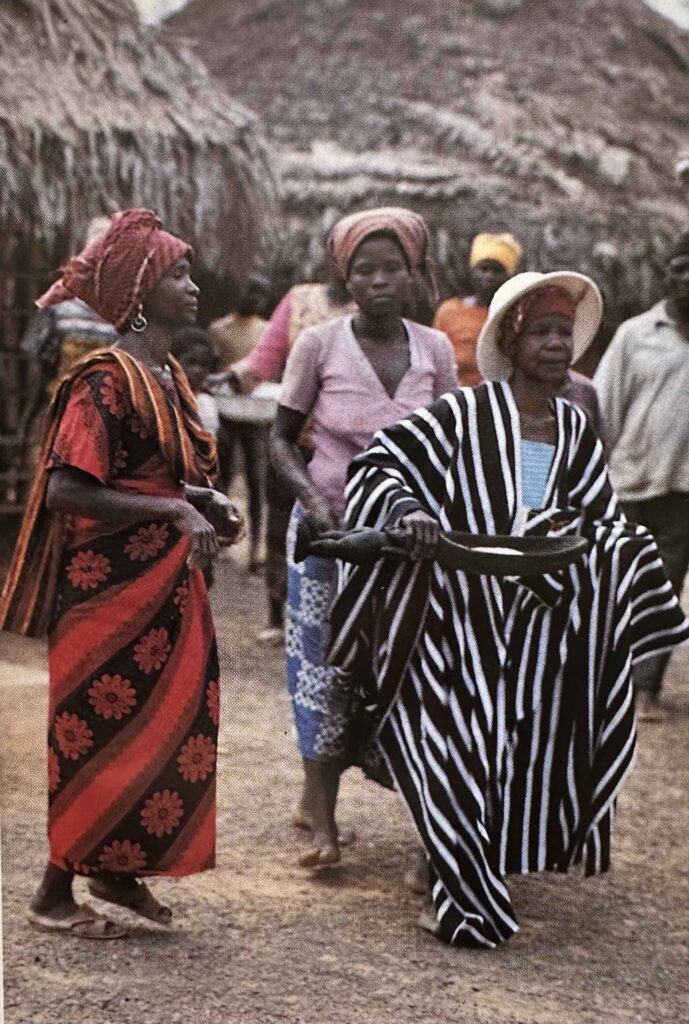

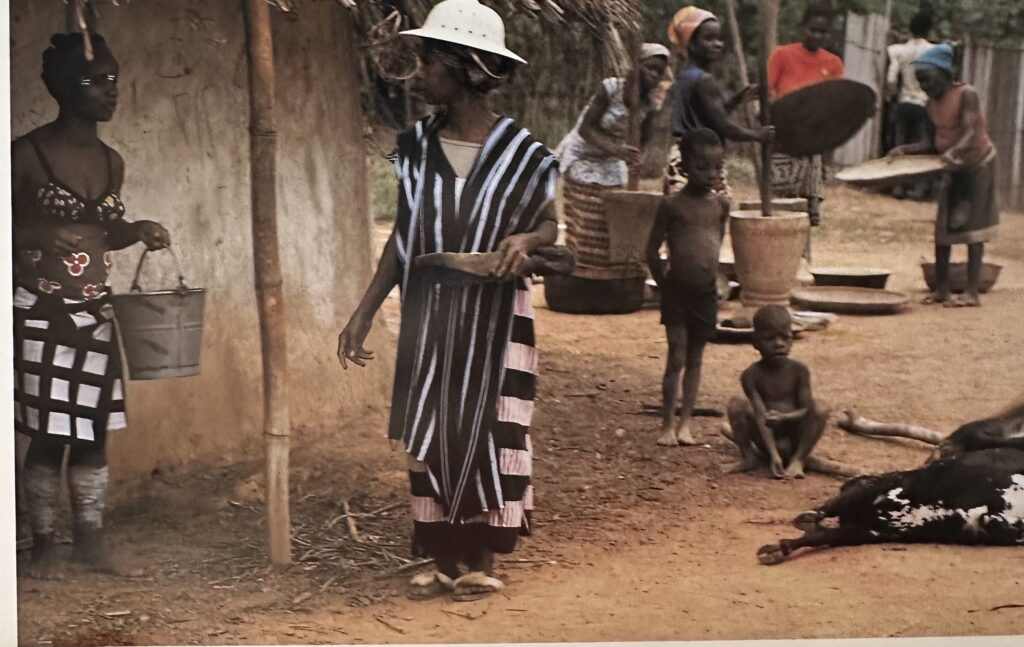

Le antilopi scolpite sono conosciute come Chiwara o come “Tijwara” – “la bestia che lavora” (“tij”: lavoro, “wara”: animale selvatico). Ricordano un essere mitico, metà uomo e metà animale, che in un passato leggendario insegnò all’uomo come coltivare la terra. Ma quando il grano abbondava, gli uomini cominciarono a sprecarlo. “Tijwara” si seppellì nel terreno e gli uomini, dopo averlo perso, scolpirono una scultura in sua memoria. “Tijwara” appare in coppie, una figura maschile ed una femminile, scolpite in legno e fissate ad un copricapo di vimini. I ballerini, curvi su bastoni di legno a simulare le zampe anteriori dell’animale, erano erano completamente nascosti da mantelli di fibre vegetali. Il significato centrale di “tijwara” originariamente era quello di incoraggiare la coltivazione collettiva della terra con la zappa. Di conseguenza si esibivano in tre occasioni: sarchiatura competitiva, danze di gioia dopo il lavoro collettivo sul campo e celebrazione annuale della società di iniziazione.

The name Sogonikun is given to a type of crest and masked figure that appeared in Wasolon and was adopted in neighboring regions. Like the Ci-wara, these crests are characteristic of a village association (ton). They appeared in the village or in the fields during the competitions in which the peasants were engaged. Groups of itinerant dancers could go from village to village (see P. Imperato, 1981). (see Bambara, Rietberg Museum 2002 page 221 figure 207

The social, economic and spiritual lives of Bamana men, in Southwestern Mali, are governed by six initiation societies collectively known as dyow (sing. dyo). The six societies are n’domo, komo, nama, kono, chi wara and kore. A Bamana man must pass through all six initiation societies respectively to be considered a rounded man with full insight into ancestral teachings and traditions.

Each initiation society has its own associated mask type (mostly zoomorphic, i.e. based on animal forms) including the chi wara (also called ci wara / tyi wara meaning ‘labouring wild animal’) dyo’s antelope agriculture headdresses. The main aim of the chi wara dyo is to educate men on farming best practices and to honour Chi Wara, the cultural hero of the Bamana, who thought the skills of land cultivation to the Bamana. Members of the chi wara dyo perform dances with masquerades to not only celebrate their hero, Chi Wara, but to also ensure the fertility of their fields and to pray to the gods for a good harvest. The celebrations are also used to publicly acknowledge the expertise of successful farmers.

NOTE: The circumcised youth ton associations and the voluntary gonzon society also make use of headdresses similar to chi wara called n’gonzon koun.

Fonte Imodara.com

The carved antelopes are known as Chiwara or “tijwara” – “the beast who labors” (“tij”: work, “wara”: wild animal). They recall a fabulous being, half man, half animal, who in legendary past thaught man how to cultivate the earth. But as grain grew abundant, men began to waste it. “Tijwara”buried himself in the ground, and men, having lost him, carved a sculpture in his memory.

“Tijwara” appear in male and female pairs on basketry caps. The dancers were bent over forelegs of wooden sticks and were completely hidden by cloaks of plant fibre.

The central meaning of “tijwara” originally was to encourage the collective farming of land with the hoe. Accordingly they performed on three occasions: competitive weeding, dances of joy after the collective field work was done and at the annual celebration of the initiation society.