Maschera ad elmo Ngontang, Cultura Fang . Metà del XX secolo. Legno, caolino, pigmenti naturali h. cm 27.

Prov. Fernandez Leventhal- NYC – e Arte Primitivo- Barcellona –

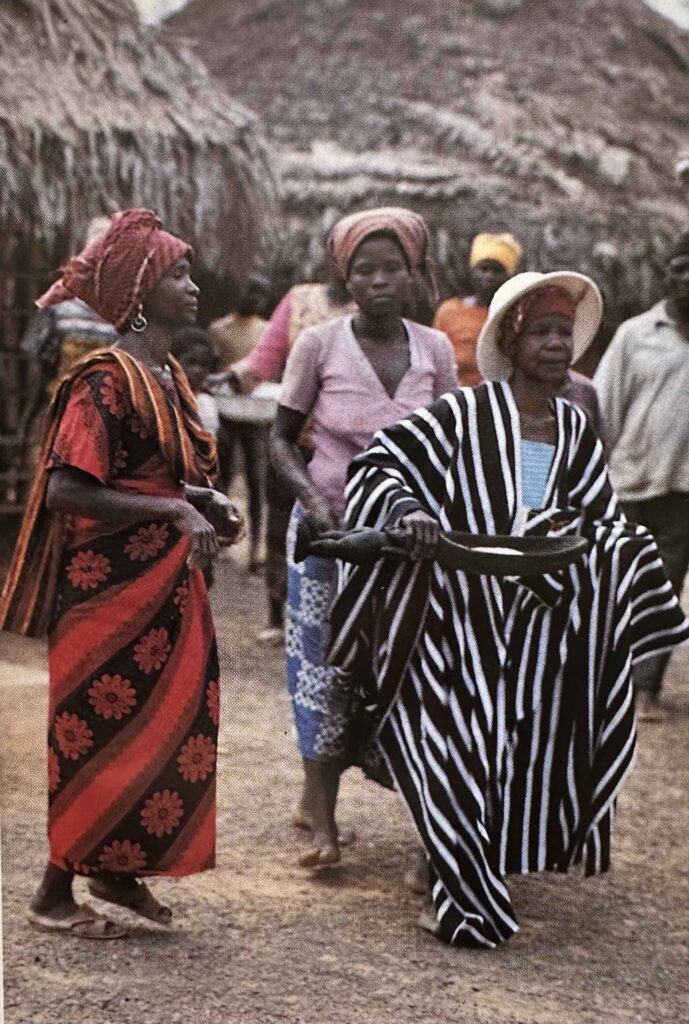

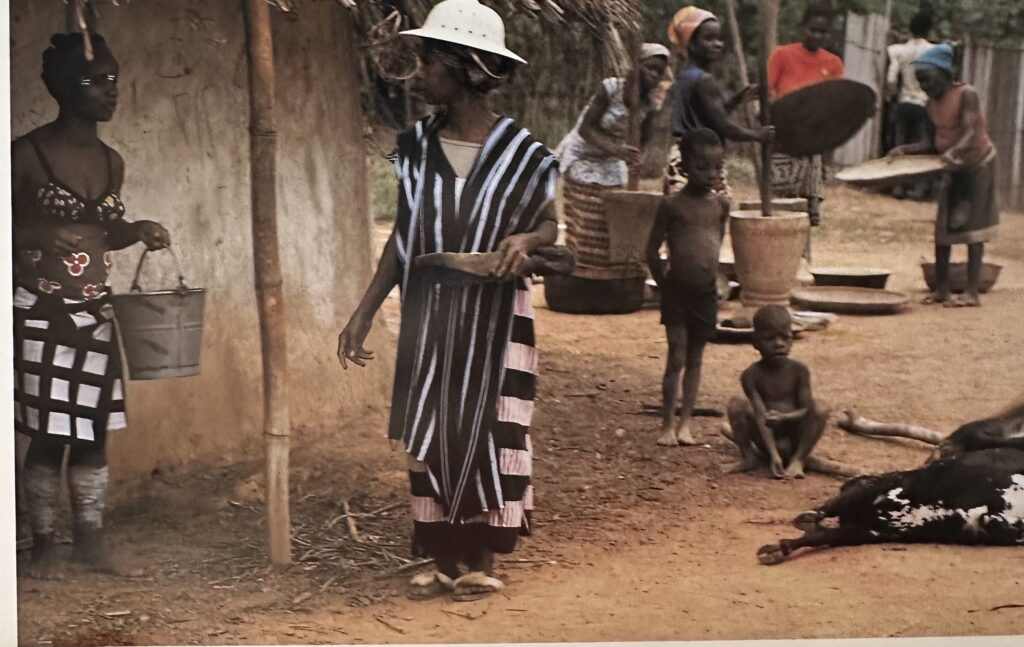

Le maschere provenienti da quello che oggi chiamiamo Gabon, e che come sempre accade in Africa è invece una terra che ospita popoli organizzati e definiti ben oltre i confini del colonialismo occidentale , sono tra le più ricercate ( e falsificate) . Ed i popoli Punu e Fang sono tra quelli che maggiormente hanno prodotto questo tipo di manufatti. Le maschere sono caratterizzate da lineamenti delicati, quasi eterei, enfatizzati dal colore bianco del caolino, e danzano in circostanze particolari. La nostra maschera ad elmo, proveniente dalle Gallerie Fernandez Leventhal di NYC e Arte Primitivo di Barcellona, ha danzato durante la cerimonia nota come Ngontang. celebrata a quanto risulta dalla comunità Fang nell’attuale Gabon settentrionale, Guinea equatoriale e Camerun meridionale fino alla metà del XX secolo . L’etimologia di ngontang (o nlo-ñgontang) sembra essere una contrazione del termine Fang nlo ñgon ntañga: testa (nlo) della fanciulla o figlia (ngon/ñgon) europea (ntañga; anche ntanghe/ntangha/ntaña) . Sulla base di questo nome e di attributi formali, si pensa che questa tipologia sia emersa in relazione alla presenza sempre più vistosa di commercianti, missionari e personale coloniale occidentali il cui numero crescente in Gabon e nelle aree circostanti ha profondamente cambiato le culture locali tra la metà e la fine del XIX secolo secolo. E’ suggestiva la teoria riportata da Joshua I. Cohen, 2016 ( https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314285 ) secondo cui “ Durante e prima di questo primo periodo coloniale, si dice che i Fang ed altri popoli equatoriali e dell’Africa centrale abbiano visto connessioni – o abbiamo addirittura confuso – tra occidentali ed esseri soprannaturali. L’aspetto fisico insolito, le nuove tecnologie e la presenza violentemente dirompente di europei e americani nella regione hanno senza dubbio contribuito a questa credenza, così come l’associazione tra gli occidentali e l’acqua ( ad esempio dovuta dal fatto che essi arrivavano dall’altra parte dell’oceano, territorio ignoto alle popolazioni locali ) così come il colore bianco della pelle, colore associato nella tradizione locale con gli spiriti e la terra dei morti. I lineamenti delicati e le carnagioni chiare dei volti delle maschere ngontang suggeriscono quindi qualità sia femminili che ultraterrene.” Penso sia certamente una prova del valore narrativo delle manifestazioni creative africane, sempre tese a comprendere il nuovo, tradurlo nel proprio linguaggio estetico ed interiorizzarlo mediante quell’alfabeto fatto di segno, colore, materia che sono le maschere ed il loro uso dinamico. Si spiega così ad esempio anche la presenza nella iconografia Baulè della figura dei Coloni, ed in genere di elementi tipicamente occidentali. Per quei popoli, ed in genere per le culture extraeuropee, l’arte è indagine della realtà quotidiane e di stati di coscienza, con il fine di governare la complessità della vita. Tornando al nostro casco Fang, sempre secondo Cohen “ la presenza di più volti ( nel nostro caso quattro) può servire per indicare poteri di percezione accresciuti nel regno degli spiriti e, se integrati in un insieme di costumi, per impressionare il pubblico…( inoltre ) ..una didascalia del 1917 pubblicata in riferimento a un’altra maschera ngontang nella collezione del Met (1979.206.24) nota che la maschera ballava “nelle notti di luna piena”. Pur non essendo certo, forse questo riflette l’ associazione fatta dai Fang tra la femminilità ed i cicli della luna: i motivi lunari spesso adornano i volti delle maschere ngontang”.

Ngontang helmet mask, Fang Culture. Mid 20th century.

Wood, kaolin, natural pigments h. 27cm.

Prov. Fernandez Leventhal- NYC – and Arte Primitivo- Barcelona –

The masks from what we now call Gabon, and which as always happens in Africa is instead a land that hosts organized and defined peoples far beyond the borders of western colonialism, are among the most sought after (and falsified). And the Punu and Fang peoples are among those who mostly produced this type of artefacts. The masks are characterized by delicate, almost ethereal features, emphasized by the white color of the kaolin, and dance in particular circumstances. Our helmet mask, from the Fernandez Leventhal Galleries in NYC and Arte Primitivo in Barcelona, danced during the ceremony known as Ngontang. reportedly celebrated by the Fang community in what is now northern Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and southern Cameroon until the mid-20th century. The etymology of ngontang (or nlo-ñgontang) seems to be a contraction of the term Fang nlo ñgon ntañga: head (nlo) of the European maiden or daughter (ngon/ñgon) (ntañga; also ntanghe/ntangha/ntaña) . Based on this name and formal attributes, this typology is thought to have emerged in connection with the increasingly conspicuous presence of Western traders, missionaries, and colonial personnel whose growing numbers in Gabon and surrounding areas profoundly changed local cultures among the mid to late 19th century. The theory reported by Joshua I. Cohen, 2016 ( https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/314285 ) according to which ” During and before this first colonial period, it is said that the Fang and other Equatorial and Central African peoples have seen connections – or have even confused – between Westerners and supernatural beings. The unusual physical appearance, new technologies and the violently disruptive presence of Europeans and Americans in the region have undoubtedly contributed to this belief, as well as the association between Westerners and water (for example due to the fact that they came from other side of the ocean, a territory unknown to the local populations) as well as the white color of the skin, a color associated in local tradition with spirits and the land of the dead. The delicate features and pale complexions of the faces of the ngontang masks thus suggest both feminine and otherworldly qualities.” I think it is certainly proof of the narrative value of African creative manifestations, always aimed at understanding the new, translating it into their own aesthetic language and internalizing it through that alphabet made up of signs, colours, materials which are masks and their dynamic use. This also explains, for example, the presence in the Baulè iconography of the figure of the Coloni, and in general of typically Western elements. For those peoples, and in general for non-European cultures, art is an investigation of everyday realities and states of consciousness, with the aim of governing the complexity of life. Going back to our Fang helmet, again according to Cohen “the presence of several faces (in our case four) can serve to indicate increased powers of perception in the realm of spirits and, if integrated into a set of costumes, to impress the public… (moreover ) ..a 1917 caption published in reference to another ngontang mask in the Met’s collection (1979.206.24) notes that the mask danced “on full moon nights”. While not certain, perhaps this reflects the association made by the Fang between femininity and the cycles of the moon: lunar motifs often adorn the faces of ngontang masks

Giuliano Arnaldi, Onzo 18 maggio 2023