Fin dall’uso delle cortecce battute, e poi con l’invenzione dei telai, i tessili portano il segno e la responsabilità di narrare storie ancestrali, quelle di cui gli esseri umani hanno bisogno da sempre per affrontare, e provare a capire l’avventura della vita.

E luoghi lontani, diversissimi per tradizioni e culture, si ritrovano a condizionarsi reciprocamente mediante “oggetti parlanti” come i tessuti.

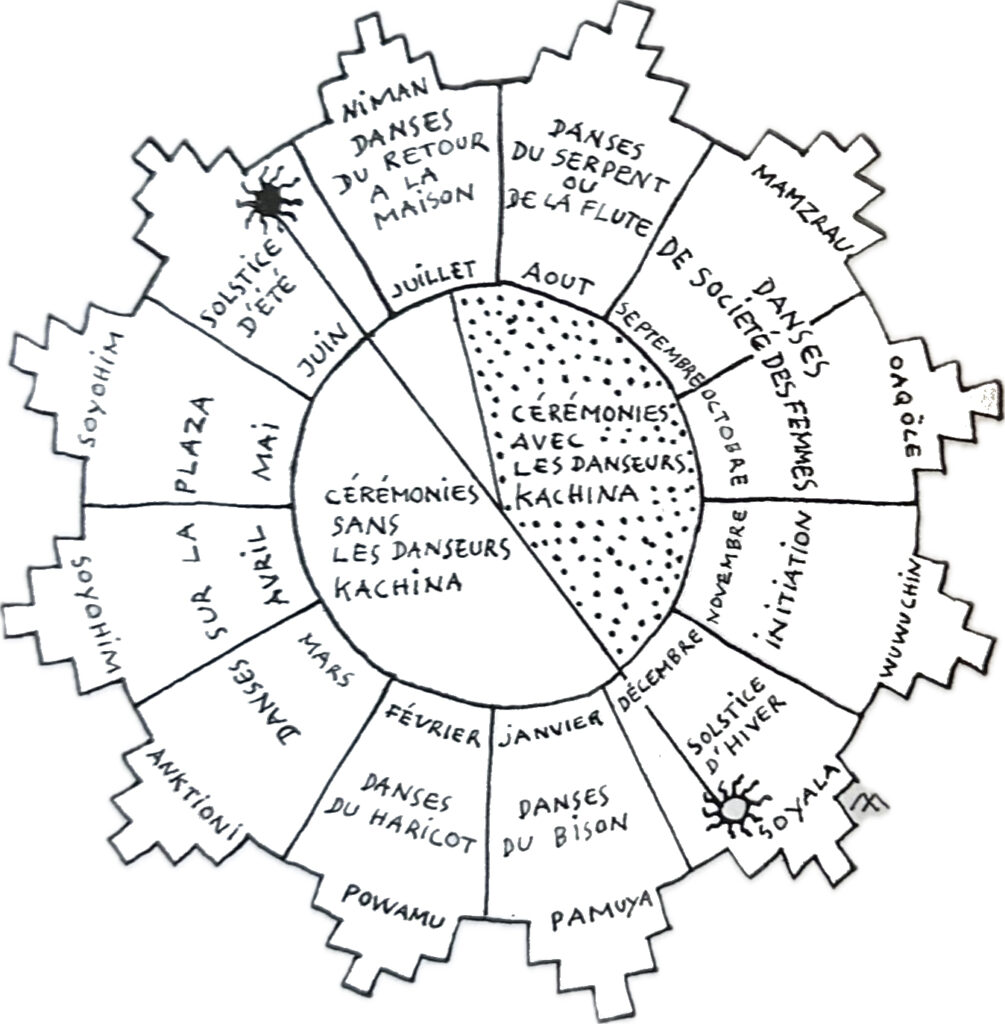

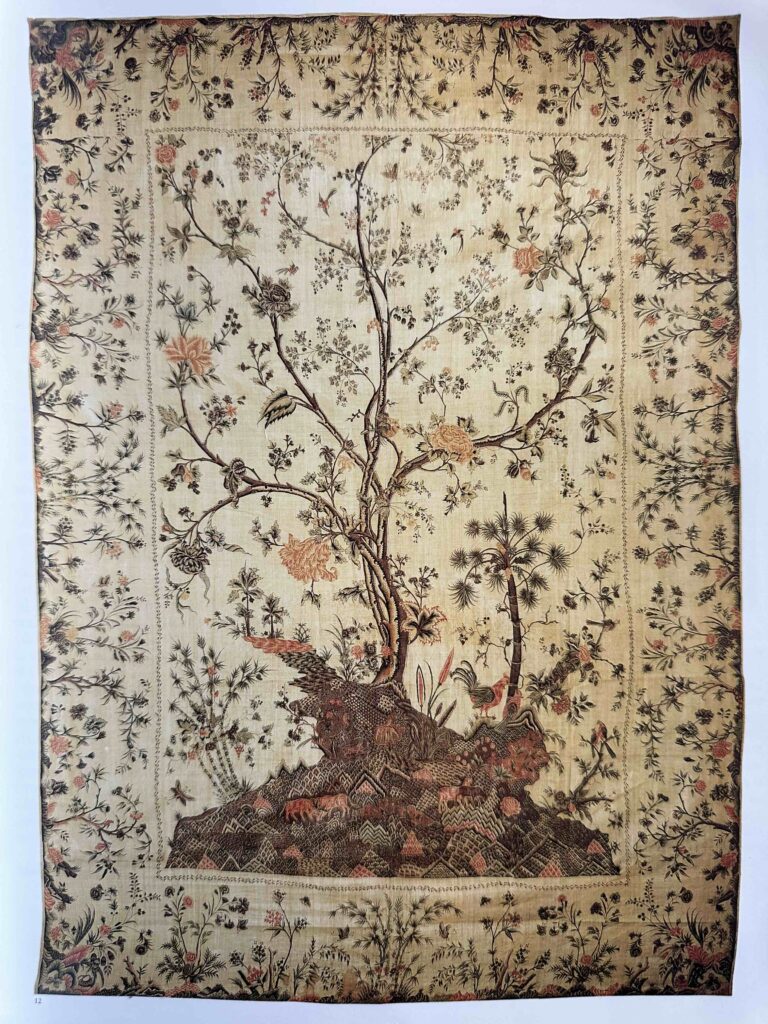

Il caso, il fato ( se preferite il destino, la Provvidenza..) crea spesso sinergie sublimi. Possiamo in questo senso dire che i Mezzeri Genovesi, simbolo di appartenenza e identità della Superba, sono in realtà figli di appartenenze ed identità lontanissime, sono figli degli antichi Palamponi prodotti in India. Il palampore è un tessuto decorato a mano proveniente da quelle remote regioni, realizzato per il mercato estero nel XVII e XVIII secolo, specialmente per l’Europa. Il nome deriva dalla parola hindi palangposh, che significa “coperta” o “copriletto”. Questi tessuti di cotone dipinti e tinti erano popolari come coperte da letto e drappeggi murali, e sono spesso caratterizzati dal motivo dell’albero della vita, con una ricca decorazione di fiori e uccelli. In realtà a loro volta vennero originati da tessili più antichi, caratterizzati da un forte valore simbolico. E’ interessante approfondire il fatto che la più tipica raffigurazione sia l’Albero della Vita, normalmente affiancato da due uccelli definiti “guardiani che si fronteggiano; l’Albero della Vita, Axis Mundi, è noto fin dal IV Millennio a.C. . Appartiene a quel poderoso complesso di riti, simboli e miti anche conosciuto come “ simbolismo del Centro” (1) che lega l’Albero Cosmico ai culti della Grande Madre Terra: sia la donna sia l’albero danno frutti, generano vita, e tutto ruota attorno alla loro centralità. Nella tradizione Cristiana è al centro del Paradiso Terreste, al principio del tempo, unisce l’ Alfa all’ Omega . Gli uccelli possono invece rappresentare sia le anime di defunti che ascendono o discendono ai vari livelli cosmici, o la dualità nell’anima individuale contrapposta allo spirito universale o coscienza pura . (2, pag. 20) . Un simbolo familiare, punto istintivo di contatto tra Oriente ed Occidente. E l’ennesimo esempio della evidenza archetipale e metaforica dell’immagine, che si fa narrazione esistenziale , riconoscibile in ogni tempo e in ogni luogo, nei Palamponi Indiani come nei Mezzeri Genovesi.

Il mezzero

Fin nel nome il Mezzero viene da lontano: Il termine “Mizar” deriva dall’arabo ميزر (mīzar), che significa “cintura” o “copertura”, ed è il nome della stella zeta Ursae Maioris nella costellazione dell’Orsa Maggiore.La stella Mira è visibile anche come una stella doppia, con il compagno “Alcor”, e le due erano anche note come “cavaliere” e “cavallo”; l’antica parola Mizar potrebbe essere diventata “Merak” con Giulio Cesare Scaligero nel XVI secolo, per diventare poi mezzero.

La storia dei Mezzeri nasce come storia di oro e spezie. Fin da tempi immemorabili i “viaggiatori di commercio “ dell’epoca, gli arabi, barattavano le stoffe indiane con merci che consideravano più pregiate, sia nelle isole dell’Estremo Oriente sia in Persia, Egitto e Africa, in questi casi con avorio, oro e anche cavalli… Quando nel commercio arrivò la concorrenza europea, ovvero intorno a XVI secolo, e le merci presero la via dei mari il fascino esercitato dai quelle stoffe fantasmagoriche stampate con tecniche antiche si diffuse. Prima gli Olandesi, poi gli altri europei iniziarono a farne commercio sempre più intensivo e, visto il successo commerciale, crearono centri di produzione diretta. Non credo che la riproduzione di quelle forme, di quei colori, avvenisse in modo consapevole rispetto al significato che essi avevano nei tessuti originali; probabilmente fu solo la loro evidente bellezza a fare la fortuna di quei tessili così inusuali per noi, anche se alcune forme archetipali, come il già citato Albero della Vita, risultavano certamente familiari; in genere l’iconografia Indiana, ben più complessa, venne ragionevolmente riprodotta o sostituita con elementi decorativi più vicini al gusto europeo. Nella produzione diretta realizzata da manodopera orientale su ordine europeo la scelta dei colori, ad esempio, veniva fatta sulla base della loro gradevolezza. Per la verità anche le stoffe indiane vennero contaminate con elementi segnici provenienti da altre culture; erano già presenti figure riconducibili al dragone cinese o, nelle bordure, le palmette tipiche della tradizione persiana nella produzione più antica, e bisogna aggiungere che la contaminazione iconografica tra India ed Europa fu reciproca; troviamo tessuti realizzati in India secondo il gusto occidentale e tessuti prodotti in Europa e particolarmente a Genova, evidentemente orientaleggianti. ( 2, pag. 76)

Genova e i mezzeri.

“L’intensa attività commerciale legata alla presenza del porto aveva favorito il sorgere di frequenti scambi di merci con alcune aree del Levante da cui venivano importati filati, tessuti e materiali per la tintura. Grazie a questi contatti con i porti medio orientali, la presenza in città di manufatti tessili provenienti dall’India è molto precoce rispetto alla loro diffusione in Europa. Nell’ottica di questa ricerca diventa più interessante analizzare gli arrivi di tessuti indiani a partire dal Cinquecento, poiché nel corso di quel secolo ha inizio il coinvolgimento diretto degli europei in questo settore.

Le indagini svolte in tale direzione hanno permesso di verificare come la circolazione e l’impiego a Genova di tessuti orientali in genere e più specificamente indiani si possa anticipare di almeno un secolo, rispetto a quanto si era fino ad ora riscontrato; similmente si è potuta constatare la frequenza con cui era usata fin dal XVI secolo la parola mezzaro. Varie citazioni documentarie cinquecentesche fanno esplicito riferimento a tessuti, talvolta denominati mezzari o meizari, provenienti dall’India: quando vengono venduti all’asta i beni del ricchissimo Gomez Soarez de Figueroa – ambasciatore di Carlo V a Genova dal 1529 al 1549 e personaggio di grande rilievo nell’ambiente cittadino in quel periodo di grande espansione nell’economia genovese e di rafforzamento dei legami politici e finanziari con la Spagna – insieme con il suo guardaroba fornitissimo figurano «meizari due Indiane»’. Anche nell’inventario dei beni di Leonardo Cattaneo – Doge della Repubblica dal 1541 al 1543 – redatto nel 1577 sono elencati: «mezzano turchino»; «mezari tre de bambaso»; «mezaro di seta morella e rossa». Per citare qualche altro esempio relativo alla diffusione dei mezzari a Genova nel1584 due «mezari» rossi sono annoverati nell’inventario dei beni di Agostino Carroccio e nel 1587 fra gli arredi di casa di Gio Batta Pittaluga è citato «uno mezaro di Levante»*. ( 2, pag. 67)

Su finire del XVII secolo sono gli Armeni ad essere protagonisti attivi nella produzione e nel commercio di questo tipo di stoffe, arrivando via Marsiglia a Genova. Nel 1690 l’armeno Gio Batta de Georgiis inizia la sua attività di stampatore di stoffe a Genova, chiedendo il monopolio per dieci anni. L’inventario di un’altra famiglia di armeni residente a Genova offre una interessante panoramica sulla mole di commerci di Indiane a Genova. Espressioni dialettali genovesi come Scaparone, Mandillo ( ovvero pezza e fazzoletto) risentono di questa influenza.

Inizia e si afferma così la produzione Genovese di questi tessili, così suggestivi da essere perenne fonte di ispirazione. Se ne trova in molte case genovesi e liguri, e almeno una antica bottega tessile Genovese ne propone una serie rifatta su modelli antichi ( si veda https://www.rivara1802.it/it/news-20/i-mezzeri-genovesi-la-storia) Ma una delle testimonianze più belle della perenne suggestione che provocano questi particolari tessili è la serie di Mezzeri realizzati su disegno di Emanuele Luzzati, il cui linguaggio estetico ed evocativo trova nella originale reinterpretazione iconografica di questi antichi manufatti una manifestazione esemplare.

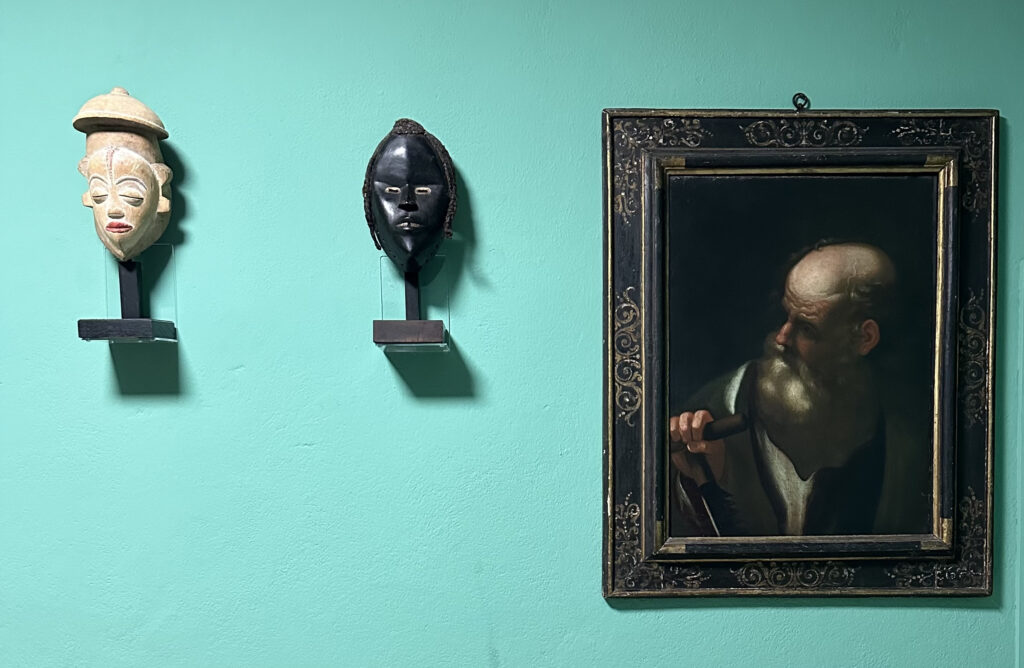

Ecco perché abbiamo scelto di porli a dialogare con le grandi opere in bronzo provenienti dalla Collezione di Paola e Giuseppe Berger nell’evento “ Cose dell’altro mondo: L’India di Giuseppe Berger ai #MagazzinidelMap.

I tre mezzeri esposti, oggi diventati una vera rarità, vennero prodotti in una serie limitata da Gildo Bagnara in collaborazione con il Museo Luzzati .

Giuliano Arnaldi, Onzo 9 ottobre 2025

Mezzaro d’autore, disegnato da “Lele” Luzzati nel 1993.

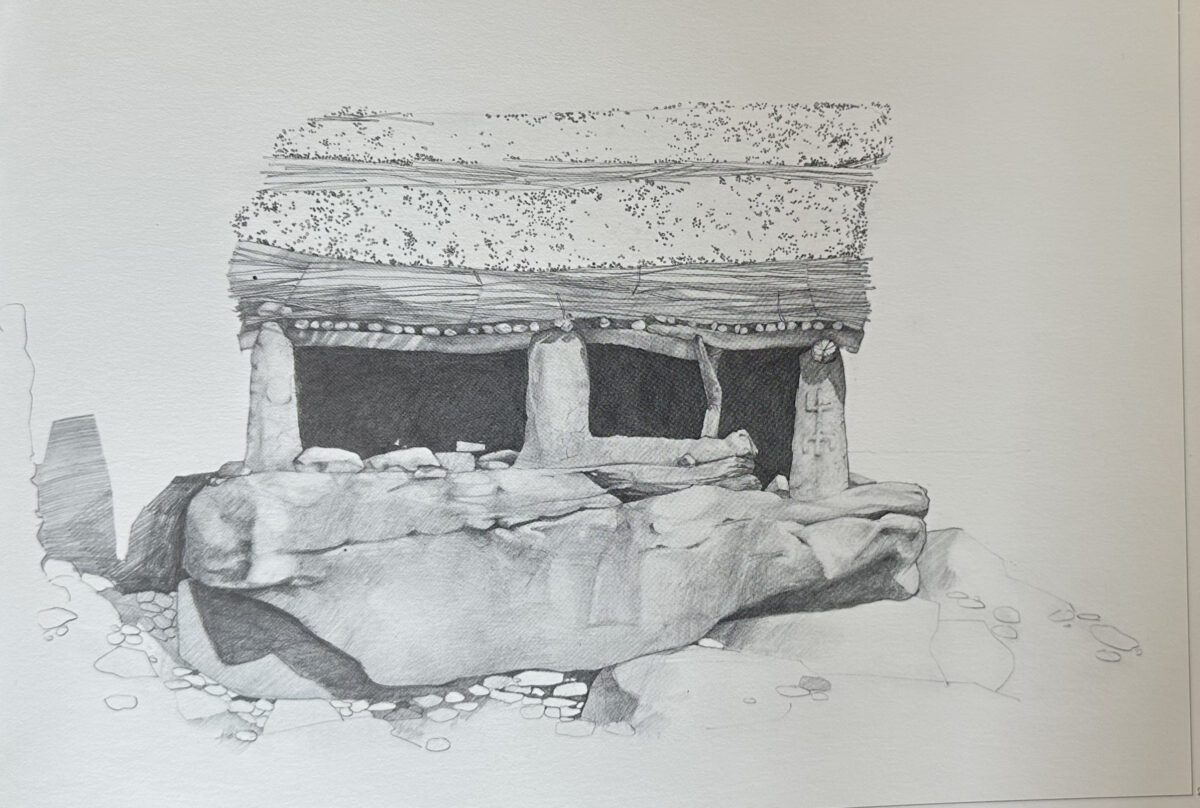

“Il Flauto Magico”

Sull’onda del grande successo della rappresentazione del “Flauto Magico” di Mozart con le scenografie di Luzzati, a Glyndebourne nel 1964, la sinergia tra questa opera e l’artista ebbe diversi frutti: un libro per bambini prodotto per il teatro della Tosse di Genova, un lungometraggio animato, la creazione di moltissime scenografie.L’opera, che l’artista amava particolarmente, divenne il tema del primo dei tre mezzari che egli disegnò. I personaggi di Tamino e Pamina, Papageno e Papagena, trovano una naturale cornice nell’ambiente dell’ “Albero della Vita”, tema tradizionale dei mezzari. La musica di Mozart diventa una meravigliosa ed equilibrata danza di colori. Il mezzaro costituisce un omaggio del maestro genovese alla musica e all’Opera, nonchè alla tradizione del mezzaro, di cui volle rispettare scrupolosamente le proporzioni e l’armonia compositiva.

Mezzaro d’autore, disegnato da “Lele” Luzzati nel 2003.

“Sogno di una notte di mezza estate”

Secondo mezzaro disegnato dall’artista genovese, è un omaggio al teatro, presentato nel 2004 in occasione di Genova Capitale della Cultura, quando furono realizzati anche i mezzari di F. Costantini e A. Verardo.

Luzzati aveva lavorato all’impianto scenografico di A Midsummer night’s dream nel 1967 all’English Opera Group, con il regista Colin Graham e le musiche di Benjamin Britten. L’opera di Shashakespeare torna a ispirare la sua creatività nel 1972, quando progetta le scenografie per la compagnia fiorentina Gruppo della Rocca e il regista Egisto Marcucci. Sullo sfondo dell’ Albero della Vita, qui vestito da un’esplosione di foglie di un’incredibile varietà di verdi – che arricchiscono anche la cornice esterna – affollano il sottobosco creature magiche, folletti, animali, bambine con le guance arrossate, fatine e cantastorie. Luzzati si mantiene fedele all’immagine del mezzaro classico, ma ne cambia i contenuti, popolandolo dei suoi personaggi gioiosi e assimilandolo ai paesaggi della fantasiosa e “silvestre” opera shakesperiana.

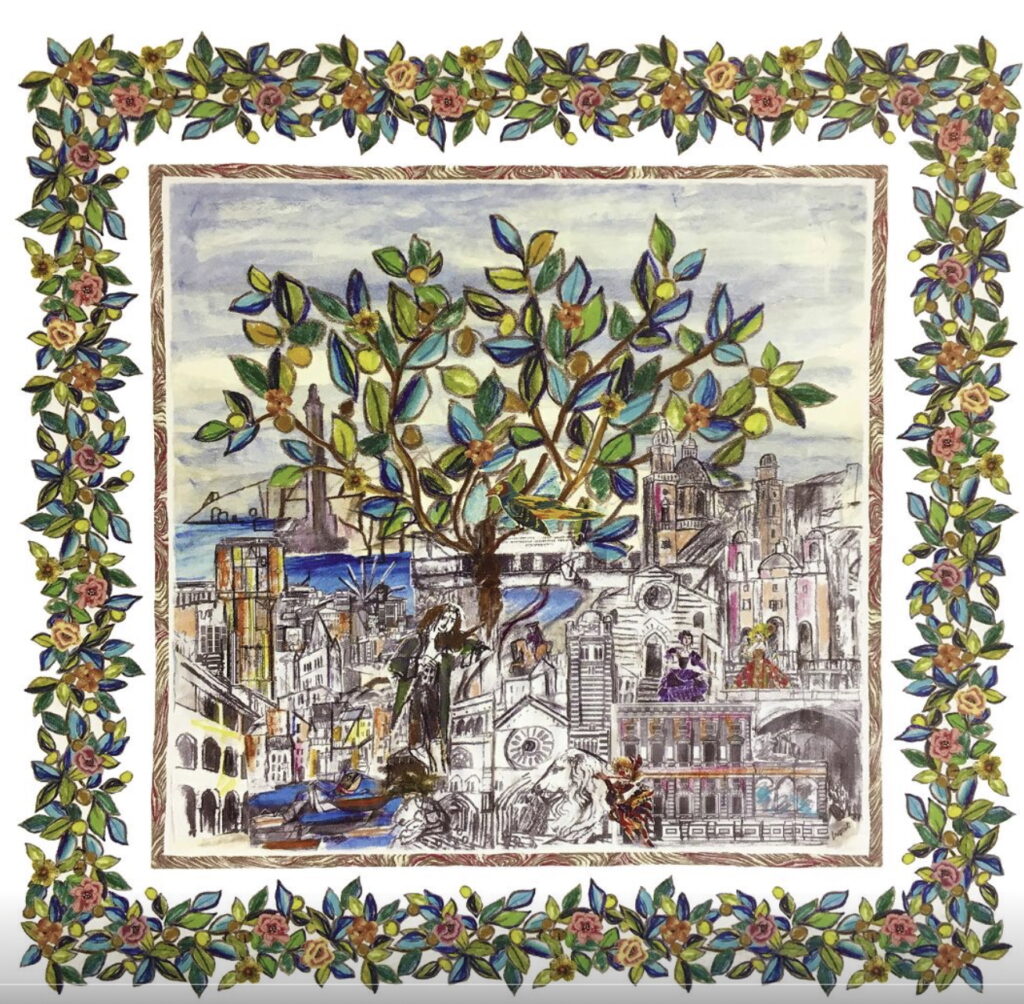

Mezzaro d’autore ,Genova di tutta una vita.

Terzo – splendido – mezzaro del maestro “Lele” Luzzati, prodotto nel 2015, stampato in digitale su percalle di puro cotone.

Dopo aver disegnato due mezzari, nel 1993 e nel 2004, senza riferimenti diretti alla città di Genova, diversamente da quelli di F. Costantini e di A. Verardo del 2004, l’artista nel 2006 espresse il desiderio di rappresentare in un ultimo mezzaro la sua città, che amava totalmente. Ma nel 2007 morì. Solo dopo alcuni anni fu possibile recuperare il suo disegno originale e portare a compimento la sua trilogia.Il titolo è una citazione della poesia Litania di Giorgio Caproni, che descrive una

“Genova Verticale

vertigine, aria scale”

Anche Luzzati dichiara:

” Genova riesce sempre a stupirmi: ogni giorno scopro qualcosa di nuovo, che non avevo mai osservato. […] Genova è un mondo aggrovigliato […] “.

E’ la stessa idea alla base del cortometraggio animato Genova, sinfonia della città (diretto e scritto da Luigi Berio, pubblicato da Nugae nel 2005) a cui rimandano i disegni degli edifici, come anche la figura di Paganini, che suona al centro del mezzaro. Tra gli altri personaggi che popolano la scena, ecco anche Papageno, che contibuisce con il Flauto magico alla sinfonia.

Tra gli edifici – tra i quali sorge l’Albero della Vita – si possono riconoscere la commenda di Prè, il Campanile delle Vigne, la Cattedrale, la Basilica di Carignano, il Bigo, e l’ascensore di Castelletto, che Luzzati definisce ” il mezzo migliore, più teatrale, per abbracciare Genova tutta intera. ” Non a caso qui a fianco possiamo scorgere uno dei rari autoritratti di Luzzati, affacciato alla finestra della sua casa di via Caffaro dove è nato e sempre vissuto.(3).

Per un approfondimento sul tema del rapporto tra Lele Luzzati e il Mezzero si veda M. Cataldi Gallo, a cura di, Luzzati e i mezzari genovesi, Il Canneto Editore, Genova 2015

- La figura del Centro Sacro è antica quanto l’uomo e, sin dalle prime forme di conoscenza simbolica, esprime il luogo eletto per l’incontro con il divino, lo spazio vitale in cui si manifesta il trascendente. Essa, infatti, ha un centro giacché rappresenta il principio da cui tutte le cose sono state generate, ed è sacra in quanto riflesso dell’Essere Supremo, nell’accezione generale di divinità ultraterrena. Ogni civiltà, sin dai primordi dell’umanità, possedeva una propria concezione di sacer, termine latino che esprime “ciò che appartiene ad altro”, che pertiene in tal modo ad un ordine soprasensibile, numinoso. fonte https://www.indaginiemisteri.it/omphalos/

- con il n. 2 seguito dalla indicazione della pagina si rimanda alla più interessante pubblicazione sull’argomento: Cotono stampati e Mezzeri, dalle Indie all’Europa, di Margherita Bellezza Rosina e Marzia Cataldi Gallo ( Sagep, 1993). Da qui ho attinto gran parte delle informazione contenute in questa scheda

- rivara1802.it